“The path to racial justice in this country has never been linear. You have moments of progress and then resistance and things get knocked back. It’s more like a zig zag,” said Orange and Chatham County Public Defender James. E. Williams Jr. “That at least in part explains what happened with the election of Donald Trump; this sort of backlash stemming from the racial anxiety of having a black president and a black family in the White House. That’s part of our history. It doesn’t make it right, but it is historically predictable.”

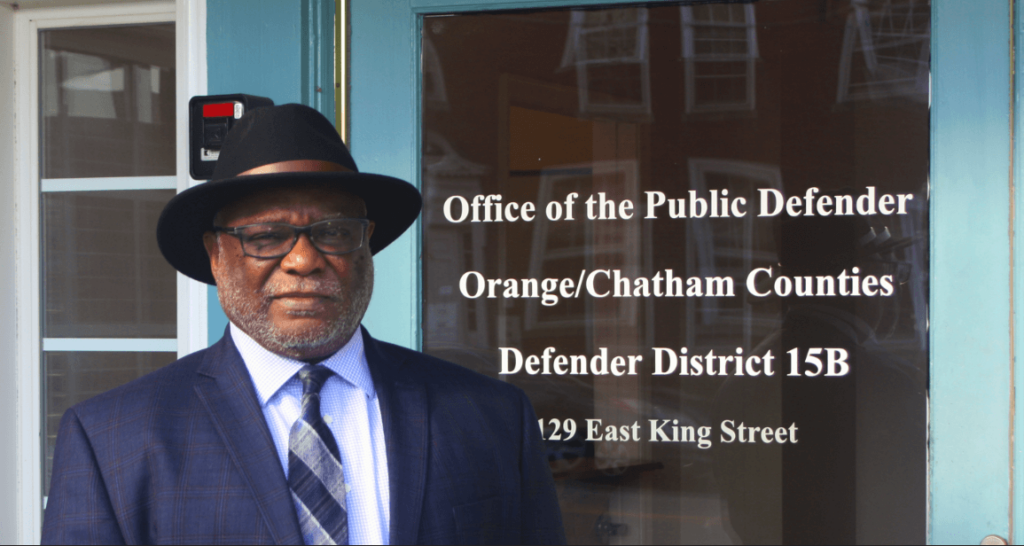

Williams has been the public defender since 1990. He uses his position and status to advocate for criminal justice reform. His office, which consists of nine attorneys and five support staff, represents clients in cases ranging from traffic offenses to first-degree murder.

Williams was instrumental in establishing the North Carolina Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Criminal Justice System and currently is a member of the board of directors. He is also founder and former chair of the North Carolina Public Defenders’ Association Committee on Racial Equity.

“As public defenders, we interact with clients most impacted by our criminal justice system. Most of our clients are people of color. We know their difficulties; we know their stories. We can articulate that. We care. We have to be a part of the solution.

“I’m of the opinion that lawyers – including judges, prosecutors, criminal defense lawyers, members of the civil bar – all have a duty to create a fairer and more just criminal justice system,” Williams continued.

“There is fairly robust, bipartisan agreement that our criminal justice system is too massive. It is too costly. It is damaging to the democratic fabric of our society. We are ethically and morally bound to try to improve upon a system that is flawed. We should be aware of the magnitude of harm and pain that it inflicts on not just those in jail or prisons but also their families and communities.

‘I Was Marked’

Williams was born in 1951 in Plymouth, North Carolina. A grandson of sharecroppers, Williams saw his father, James Sr. and his mother, Annie, under the thumb of Jim Crow.

“My father worked at a pulp factory for over 30 years. He knew how to do almost everything. When they hired new supervisors, he would train them, but he was not allowed to be supervisor because he was black.

“Despite the fact that my mother had a high school degree, the best job she could find was being the help,” Williams continued. “Taking care of cleaning white folk’s homes and taking care of their children.”

Williams recalled buying a few pennies worth of candy at a one-room country store when he was 8 or 9 years old. As he was leaving a thunderstorm rolled in. The white store owner insisted that Williams leave and go out into the raging storm. “I don’t remember his exact words, I know the tone in his voice and the look in his eyes,” he recalled. “That was the first time I truly knew that I was marked.”

Around the time of the Voting Rights Act of 1964, 12-year-old Williams attended a nonviolent civil disobedience training workshop hosted by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The event was marred by a cross burning by the KKK. But it was marked by a riveting keynote speech on racial equality by civil rights attorney Floyd B. McKissick who subsequently became the national director of CORE before founding Soul City in Warren County in 1969.

“McKissick whipped the crowd up with a fervor with his passionate speech and dialogue. He was sweating and it was almost as if there were spittles of foam forming around his lips. I was just captivated,” recalled Williams. “I think it was probably at that moment that the initial thought of being a lawyer entered my mind. I was thinking about ways I could most contribute to creating this beloved community that Dr. King dreamed of.”

Williams attended Duke University when it was one of the North Carolina colleges under pressure to admit African- Americans or lose federal funding. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in political science and earned his Juris Doctor from the Duke School of Law.

Battling Implicit Bias

“Part of my work is making sure we are all more cognizant of implicit bias, so that we don’t unwittingly contribute to the problem. Sometimes people with the best of intentions, who disavow racism, who aspire to be fair make unconscious decisions that are racially biased.

“Implicit bias rears its ugly head when you do things too fast,” he continued. “Take your time. When you have eight or 10 clients, and you have to make decisions quickly, take a moment, step back, and make sure you’re deciding based on the appropriate factors.”

Williams is involved with the Orange Bias Free Policing Coalition. “We’re making progress in regulatory traffic stops and have moved our focus onto evaluating who poses a public safety risk when you’re out patrolling rather than who has a dim taillight. It’s not just the client who comes in our door; it’s trying to reduce the number of clients that have to come through the door, especially for reasons that might be based on race.”

Three Wars

Williams blames the widespread incarceration of young African-Americans, in part, on a lack of employment opportunities.

“In the early ’60s, when we were talking about the War on Poverty, we were on the right track. But somehow that got high-jacked. People began to see civil rights activism as a law and order problem. The War on Poverty became a War on Crime. When the media and Reagan sensationalized the drug problem, a War on Drugs was declared. So, a war was declared on the very people who most needed help; they were disproportionately people of color.”

Source of Inspiration

Today, Williams is married with two grown children. He enjoys reading civil rights history, listening to jazz, and watching classic movies.

“Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk are some of my favorites. I love jazz. For some people, it’s meditation; jazz does something similar for me.”

Free time is also spent trying to get people from various backgrounds and disciplines to the table to converse about race and justice. He is an impassioned and eloquent speaker. His words are carefully measured and bear the cadence and tone of the church-steeped civil rights leaders of his youth like Dr. King.

“Quite oft en I find myself in situations that would make a younger me angry,” he said. “I say, let’s make this a source of inspiration. Freedom is a constant struggle. I find gratification in the struggle itself. The fact that I am engaged and attempting to make a difference, makes a difference.”