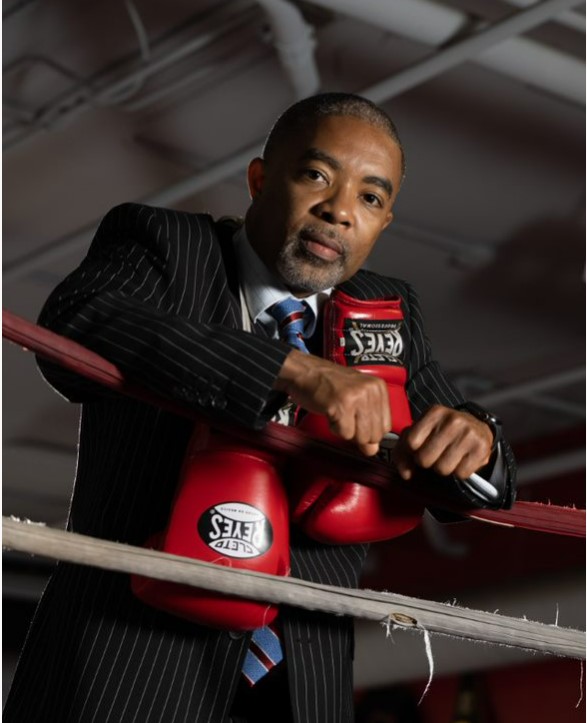

Wake County attorney Patrick Roberts danced smoothly around the ring at Jawbreakers Boxing Gym in Raleigh as he pounded training mitts worn by trainer Remy Fullwood. Roberts is getting back into his regular training routine after a long hiatus while the gym was closed during COVID.

“Boxing for most people is just brutal sport,” said Roberts, “but there’s so much strategy involved. There’s footwork. There are combinations. There’s countering. There’s figuring out your opponent’s weaknesses, so you can attack those weaknesses without being attacked yourself.”

Former professional boxer Fullwood is the owner of Jawbreaker and the son of former Superior Court Judge Ernest B. Fullwood. In the ring surrounded by Muhammed Ali posters, Fullwood said Roberts’ best punches are his left hook and solid combination.

On a global scale, a solid combination describes Roberts as a man, a boxer, and a lawyer.

Patrick Roberts launched his Raleigh-based criminal defense firm in 2007. He now has 10 attorneys working in offices in six cities handling criminal law, family law and estate planning. In 2019, he founded a personal injury practice with Ranchor Harris, an attorney he met through a mutual trainer. The criminal law practice handles large cases such as drug trafficking, murder, and a heavy emphasis on sex crimes. The personal injury firm does catastrophic accidents, trucking cases and wrongful deaths. The firm is also active in the burgeoning Camp Lejeune water contamination litigation.