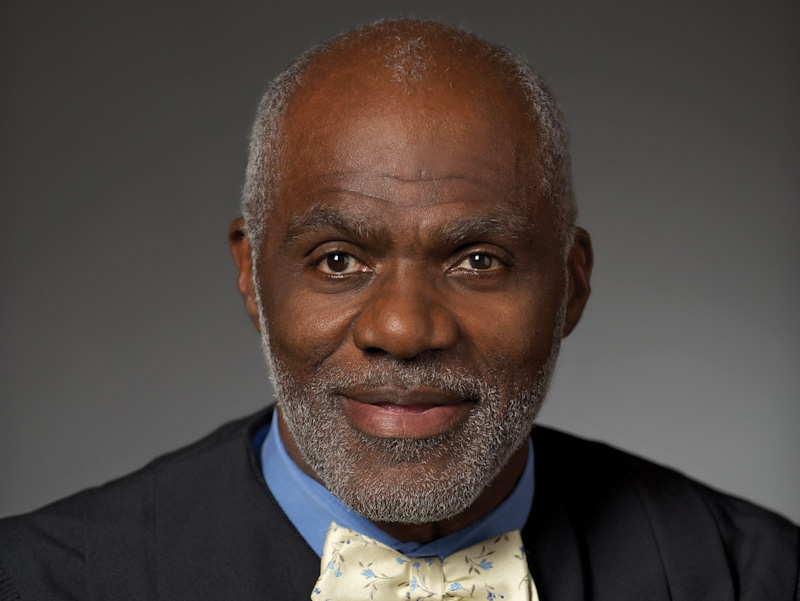

My father, Alan Page, has reached the pinnacle of success as a football player, a philanthropist, and as a jurist on the Minnesota Supreme Court. Whenever I am out in public with him, people always come up to him to say hello, ask for a photograph or an autograph. Looking back over the last 30 years, it is hard to believe that his ascension to the Minnesota Supreme Court almost did not happen.

“It was incredibly disappointing” my father said to me to me on a recent morning walk. We were reminiscing about the obstacles he faced when he tried to run for election to the Minnesota Supreme Court, first in 1990 and then again in 1992. Gov. Rudy Perpich successfully blocked my father’s efforts to run for the Supreme Court in 1990. In July 1990, my father filed to run for Justice Glenn Kelley’s Supreme Court seat, since Justice Kelley would have been required to retire soon after running for reelection. However, Gov. Perpich made sure my father would not have the opportunity to run for election when Justice Kelley retired early, and the governor was able to appoint his replacement.

History repeated itself again in 1992, when Gov. Arne Carlson also tried to block my father’s efforts to run for a Supreme Court seat when he extended the term of Minnesota Supreme Court Justice Lawrence Yetka by two years and thereby ensured there would be no Supreme Court seat up for election. At the time, Justice Yetka was 68 years old. He wanted to serve until he reached the mandatory retirement age of 70 without running for re-election, so he could maximize his pension benefits. The governor granted Justice Yetka his wish.

However, the governor underestimated my father’s determination to fight a decision that he thought was wrong and contrary to Minnesota law. In Bill McGrane’s book, “All Rise: The Remarkable Journey of Alan Page,” Jim Finks, the general manager of the Minnesota Vikings during my father’s football career, said, “If Alan Page says he will play five more years of football at the highest level, he will do it. If Alan Page says he will run a marathon, he will do it. If Alan Page says he will become a member of the Minnesota Supreme Court, he will do it. And he will do it quietly and without a lot of fanfare and chest-thumping. He just does it.”

Because my father was determined to run for election to the Minnesota Supreme Court and let the people of Minnesota decide who the next Supreme Court justice should be, he chose to fight the governor’s decision. However, he didn’t do it quietly. On July 15, 1992, my father attempted to file as a candidate for Justice Yetka’s seat on the Minnesota Supreme Court. Page v. Carlson, 488 N.W.2d 274, 276 (Minn. 1992). As a result of the governor’s order, the Minnesota secretary of state refused to accept my father’s candidate filing. Id.

In order to challenge Gov. Carlson’s decision, my father petitioned the Minnesota Supreme Court. The petition challenged the secretary of state’s refusal to place his name on the ballot for the 1992 primary election as a candidate for the seat of Associate Justice Yetka. In a historic and unprecedented move, all the justices on the Supreme Court exercised their rights of recusal because of the potential of a conflict of interest, and a panel of retired members of the bench were appointed to decide the case. Id. at 277.

There were two issues before the Supreme Court: (1) whether it had original jurisdiction to hear and determine the case; and (2) whether a judge nearing retirement age is automatically entitled to an extension of his term of office to maximize retirement benefits. Id. On August 20, 1992, the court issued an order finding that the governor’s decision to extend Justice Yetka’s term violated Minnesota law. Id. at 282.

On the first issue, the court found that it had original jurisdiction to hear my father’s petition. It found that “the public interest requires a speedy determination whether the Governor’s order abrogating an election for Justice Yetka’s seat was improper as a matter of law and whether petitioner is entitled to have his name placed on the primary ballot.” Id. at 278.

With regards to the second issue, the court held that an “extension of a judge’s term should be granted only when it is necessary to permit the judge to serve for the minimum number of years to become eligible for a pension, but the extension should not be granted to permit a judge to maximize or enhance a pension for which the judge is already eligible, and thus avoid an election.” Page v. Carlson, 488 N.W.2d 274 at 282. Since Justice Yetka became eligible for his pension in 1989, the court ruled the governor’s extension of Justice Yetka’s term was unlawful. Id. at 281.

Upon learning of the ruling, my father was quoted in the Star Tribune as saying, “I am thrilled for a couple of reasons. I finally have the opportunity to be on the ballot, but more important, the people of Minnesota are the real winners here. The Court has said the Constitution requires elections and that the election will go forward.”

Once the Supreme Court issued its decision, Justice Yetka decided against running for re-election. However, the decision prompted other candidates along with my father to run for the open seat.

My father is reserved and quiet. Not necessarily the best traits for a candidate campaigning for any office, let alone a statewide campaign, but again my father should not be underestimated. My late mother, Diane Page, was quoted in McGrane’s book as saying, “The idea of running for office was a daunting one for him, but you should have seen him campaign. He was tireless. I don’t think there was a town in the state that he didn’t visit. Alan is very goal-oriented and focused, and he took nothing for granted.”

My father’s shyness was not the only obstacle he would have to overcome to get elected. He would also have to overcome the argument that he was unqualified, and he was relying on his reputation as an ex-football player to get elected. After being one of the two candidates to win the primary election, my father faced Kevin Johnson, an assistant Hennepin County Attorney, in the general election.

Johnson accused my father of using his reputation as a football player to win the seat and trying to buy his way onto the court. “Alan Page is a nice guy, a great football player [but] not qualified for the Supreme Court,” Johnson was quoted as saying in a Star Tribune article on September 10, 1992. Johnson also used racially coded language to suggest my father was not qualified. He charged in another Star Tribune article in October 1992, “[i]f Alan Page happens to get elected, unfortunately, it may reinforce the erroneous notion that the only way you can get minority people in positions of responsibility is by [selecting] token, unqualified people.”

The attacks appeared to be working. In a fall survey of lawyers conducted by the Minnesota State Bar Association, Johnson received support from 54% of participating attorneys and my father received support from 46% of participating attorneys.

However, my father did not let the negative campaigning deter him. His campaign slogan was “Alan Page, A Justice for All.” He took his campaign to the people of Minnesota. He traveled the state and went on radio, television, visited schools and talked to everyday Minnesotans. He answered the Johnson campaign’s criticism by talking about his 13 years of experience in private practice and in the Minnesota Attorney General’s Office where he litigated cases in district court and argued cases at the Minnesota Supreme Court.

He was endorsed by both attorneys and non-attorneys. The Star Tribune wrote this about my father when endorsing his campaign on Oct 20, 1992: “[t]he clear thinking that is one of Alan Page’s many qualifications for the state’s highest court was evident when he successfully challenged the gubernatorial extension of a Minnesota Supreme Court justice’s term and fought for an election. His keen mind, his dedication to justice and is his diverse experience in a 13-year career argue for Page’s election.”

My father campaigned hard and on election day, his hard work paid off. By an overwhelming margin, my father won a seat on the Minnesota Supreme Court. In winning the election, he became the first African American to sit on the Court and the first African American to elected to a statewide office. He was sworn in as a member of the Minnesota Supreme Court on January 4, 1993.

My father would go on to run for re-election three times and each time the citizens of Minnesota overwhelmingly re-elected him to the court. In fact, according to a Star Tribune article, in 1998, he received the most votes ever for a statewide contested race. He would continue to serve on the court until 2015 when he reached 70, Minnesota’s mandatory retirement age for judges.

While my father’s road to the Minnesota Supreme Court did not follow a normal path and was bumpy at times, his courageous decision to challenge the governor’s decision to extend Justice Yetka’s term changed history and allowed him to become “a Justice for All.”