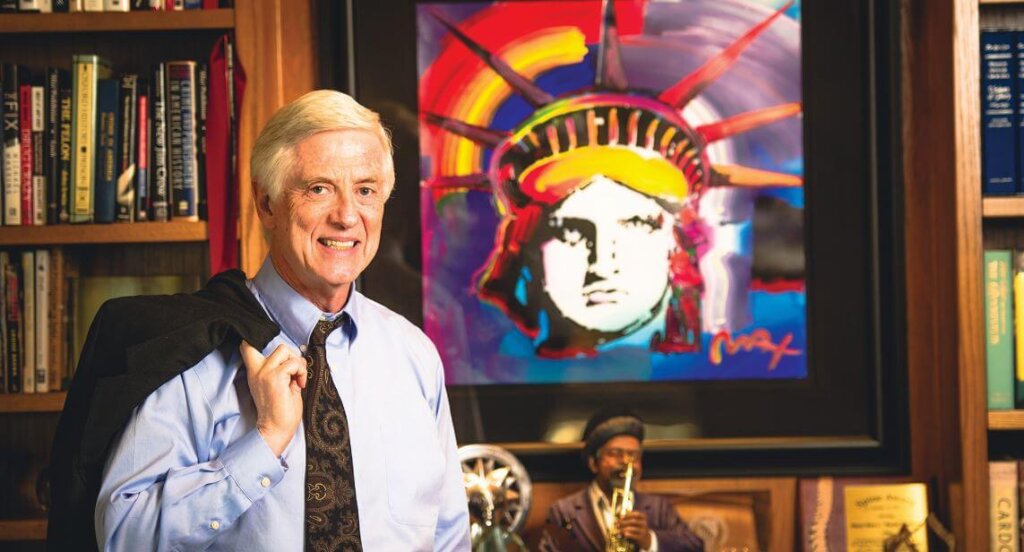

Rocky Anderson has been labeled an outspoken champion, a firebrand, a man who never shies away from a fight. He’s just as likely to quote Immanuel Kant and the Dalai Lama as Martin Luther King Jr. or St. Matthew. He advocates for human rights, was called by Amy Goodman “one of the most progressive mayors in the United States,” and is a former third-party presidential candidate. The trim, silver-haired lawyer can be unrelenting in his fervor, yet has a track record of winning and often turning adversaries into allies.

The diverse and storied path that led him to serve as of counsel for Winder & Counsel is the result of a singular, uncompromising focus.

“I am driven to fight against injustice,” says Anderson. “There is so much injustice – and it doesn’t have to be that way. Committed people and a decent government, including a system of justice that uniformly applies the rule of law, can remedy so many social, economic and environmental injustices.”

Two cases that inspired him to reactivate his Bar license present a unique opportunity to pursue justice and achieve major reforms. “I seek to find the most effective means of contributing toward positive change,” says Anderson.

He is representing the Libertarian and Green parties and their candidates in an antitrust case against the Republican and Democratic parties and the Commission on Presidential Debates. The goal is to achieve equitable, informative debates run by a nonpartisan organization, versus the bi-partisan commission, formed and controlled by the two major parties, which has controlled the debates since 1988. That’s when the debates were hijacked from the League of Women Voters, which stated, “The league has no intention of becoming an accessory to the hoodwinking of the American public.”

Rocky Anderson argues that’s exactly what has happened. “It’s one of the really devastating ways in which those two parties have continued to monopolize our political system and ultimately our government, contrary to the public interest,” he says.

Anderson sought to change the discourse of presidential politics during the 2012 election, when he spent a year campaigning for president as the candidate for the new Justice Party, which he co-founded.

“I didn’t run to win an election. I ran because it was such an essential opportunity to help raise awareness about the degradation of our democracy and our political system, which has become nothing more than a servant to the highest bidders,” says Anderson. “Third party candidates often introduce ideas that later become progressive public policies. It’s important they be heard.”

A Moral Imperative Anderson’s undergraduate studies in philosophy and politics at the University of Utah revealed a deep sense of responsibility to actively change things in the world, “especially where people without power or opportunity needed help,” he says. It was the late ’70s and global human rights atrocities, some of which were being committed in the name of democracy, alarmed Anderson. “I think from a fairly young age I had a strong sense of the personal responsibility we each have to stand up and say, ‘no’, then take action, when our government is engaged in those atrocities,” he says.

Anderson graduated with honors from George Washington University Law School in 1978 and returned to Salt Lake City to begin his legal career. For 21 years, he worked tirelessly on a tremendous variety of cases and causes, including several involving the First Amendment, civil rights, and abuses of power by corporate and government agents.

In Bradford v. Moench, Anderson was able to establish a precedent that depositors in underinsured financial institutions are entitled to the broad protections of federal securities laws.

Another important precedent, Bott v. Deland, provided far greater protections for vulnerable incarcerated people than what is provided under federal law. “That case will have lasting, real-life impacts for hundreds of thousands of people,” says Anderson.

He was lead trial counsel in several cases and successfully handled major medical and legal malpractice cases, an antitrust boycott case, and several police, jail, and prison abuse cases. Anderson also represented victims of sex abuse, as well as victims of false sex abuse accusations.

Justice in Office His work in the legal field and in several community nonprofit organizations vividly demonstrated to Anderson the flagrant disregard by many elected officials of the environment, underrepresented minority groups and economically disadvantaged people. “So I ran for Congress in 1996, then as mayor,” he says. Despite having successfully pursued many high-profile cases against the city and the police department, the Salt Lake Police Association endorsed Anderson for mayor in 1999. The union chief said, “[Rocky’s] commitment to the safety of the community, as well as to the men and women of the police force who are out on the street every day risking their lives, is clear.”

As mayor, Anderson appointed a police chief and city attorney who worked with him to implement perhaps the most comprehensive restorative justice programs in the nation. Other projects during his tenure as mayor included the creation of YouthCity, the first-ever citywide afterschool and summer program for young people; the founding of the Salt Lake City International Jazz Festival; the expansion of the light rail system; and an internationally renowned climate protection program.

He was an outspoken critic of the Iraq War and the Bush Administration, leading the charge to impeach the president and vice president, and has been a long-time supporter of marriage equality and immigration reform.

Anderson decided not to run for a third term, but instead devoted his time and energy to a larger cause – pushing elected officials to stop human rights abuses.

“A common thread running throughout the history of genocides, sex slavery, the climate crisis, and other major human rights tragedies is the fact that our elected officials are generally not leaders…. It is up to us to lead – to organize – and to make a positive difference by pushing our elected officials to do the right thing,” Anderson said in a 2006 speech.

Justice for Human Rights With his usual passion and devotion, Anderson founded High Road for Human Rights, a nonprofit organization that facilitated grass-roots activism by combining the voices of few into the roar of many. The group focused on educating and mobilizing a network of citizens concerned with human rights abuses and helping them communicate those concerns to elected officials. It targeted abuses such as slavery, torture, the death penalty, the climate crisis and genocide.

As executive director of High Road for Human Rights, Anderson testified before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee concerning executive-branch abuses of power and called for accountability for illegal torture and surveillance.

Anderson turned to the electoral process to keep human rights issues on people’s minds and consciences. He publicly renounced his membership in the Democratic Party in 2011 and co-founded the Justice Party.

After the 2012 presidential race, Anderson spent two semesters teaching at the University of Utah about the undermining of our constitutional republic and the role of the media in enlightening, and at times severely deceiving, the public.

Justice in Law After being approached to handle the lawsuit to open up the presidential debates, Anderson joined Winder & Counsel on an of counsel basis. “The Winder & Counsel firm has been remarkably supportive,” Anderson says. They have been terrific in accommodating me so that I can be more effective in what I’m now seeking to do. It makes such a difference to be around highly competent, principled lawyers who engage in a broad range of transactional and litigation work. The working environment with the people at the firm is extraordinary.”

The second case Anderson recently took involves the right to privacy and putting a check on police brutality. Anderson is again suing the city he used to lead and its police department on behalf of Sean Kendall, whose beloved dog, Geist, was unlawfully shot and killed by an officer in 2014. Anderson is confident the case will achieve major reforms in training and policies regarding the treatment of domestic animals.

“I get out of bed every morning and can’t wait to get to the office,” Anderson says. “Lawyers choose a lot of different fields to work in, but there are always exciting, rewarding ways for any lawyer to help bring about greater justice in our community, our nation and our world.”

“Change can be made, even one case at a time,” says Anderson. “Often, it seems to take far too long, and that we’re up against almost impossible odds, to change things for the better. But I’ve experienced it many times – and it is incredibly rewarding.” Stacey Closser