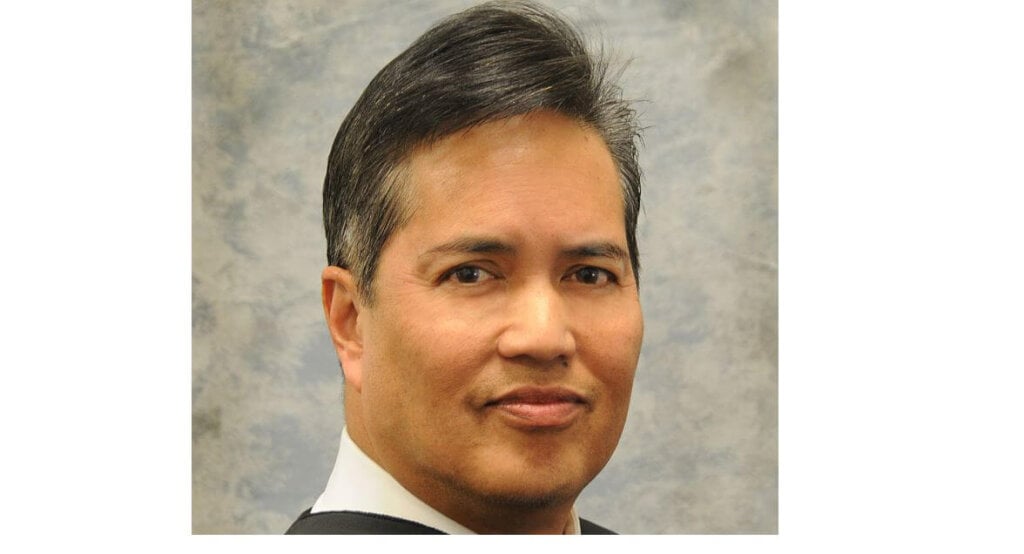

Attorney at Law Magazine Los Angeles Publisher Sarah Torres sat down with Judge Rob B. Villeza to discuss his career.

AALM: What drew you to a career in the law?

Villeza: Certainly not my background. I grew up in Echo Park in the 1960s and 1970s. It was a working class neighborhood with large immigrant families. And gangs. Education meant getting your high school diploma. My dad had three families. Even though I was the youngest of 10 children, I was the second to graduate from college and the only one to pursue a career in law. My dad was diagnosed with cancer when I was 6 (he passed when I was a junior in high school). My mom took two buses to work as an English teacher in South Central Los Angeles.

In high school, I worked after school as a mechanic apprentice and was offered a full-time position after graduation. Soon after, I enrolled in junior college to learn more about becoming a police officer. My interest in the law took off and, after participating in speech and debate, I knew I wanted to become a lawyer. I later transferred to the California State University of Los Angeles and eventually to UCLA Law School. To this day, my mom tells me that she can’t believe the same boy who would fly down the hill on anything with wheels is now a judge. I still consider myself a kid from the neighborhood.

AALM: How did you transition from your career as an attorney to your career as a judge?

Villeza: I learned to be a federal prosecutor from the best – some of whom are now judges and justices. People often think that a prosecutor’s mindset is to win the case at whatever the cost. But we were taught to do the right thing every time. That meant we had to look at cases from all angles – as a prosecutor, evaluating the strengths of your case; as a defense attorney, identifying the weakness of the government’s case; and, as a judge, looking at all of the circumstances to determine the right and fair result in the case. So, it wasn’t a huge stretch from prosecutor to judge when the shared mission is doing the right thing to achieve justice. After 23 years in the U.S. Attorney’s Office, I was ready to embrace a new challenge. My current assignment in a criminal misdemeanor court in Pomona gives me an opportunity to serve the people of the community.

AALM: Do you have any advice for attorneys trying a case before your bench?

Villeza: Even though I came from the formal decorum of federal court, I try to make the lawyers and self-represented litigants comfortable in my courtroom. It suits my personality. I don’t expect lawyers to rise every time they address the court and I don’t nail them to the lectern during trial. However, I do expect everyone to be respectful and courteous at all times.

In a misdemeanor court, we often hit speed bumps whenever I have new lawyers trying a case. It’s frustrating when new attorneys fight over every issue, prolonging the trial unnecessarily. A good trial lawyer picks the right battles. Before arguing just for argument’s sake, consider your long-term strategy. You’ll impress the judge and opposing counsel, and enhance your credibility.

AALM: What do you love about your job?

Villeza: As a federal prosecutor, I felt I made a difference going after the people who profit by smuggling large loads of drugs that end up on our streets. As a judge, I feel I’ve been able to make a difference by serving the victims of street crime or by helping those with a drug or alcohol problem in need of counseling. Even though handling a misdemeanor court might not be front page news, I find it challenging and rewarding. One of the most satisfying duties is reviewing petitions to expunge misdemeanor convictions and help someone turn his or her life around. It gives me great joy to remove the conviction, express my optimism for their future, and share in their pursuit of the American dream.

AALM: What do you find most challenging about your profession?

Villeza: As a new judge in a busy misdemeanor court, the challenge is managing the calendar and trial schedule. We can have 60 or more calendar matters on a given day with trial in the afternoon. At times, it can be challenging to give every attorney or defendant their day in court without using the time reserved for trial.

AALM: Do you have any mentors?

Villeza: My mentors in life are Senior District Judge Consuelo B. Marshall and California Appellate Justice Jeffrey W. Johnson. I served as a judicial extern for Judge Marshall when I was a second-year law student at UCLA Law School. We’ve become life-long friends. If I could emulate another judge on the bench, it would be Judge Marshall. Justice Johnson is like a big brother to me. I would not be in this position without his support. We don’t see each other as often these days, but when we do, we just pick up where we left off. He is a brilliant jurist.

AALM: Are there any changes in the legal community that you are excited about?

Villeza: I’m very excited about the recent efforts to improve diversity on the bench. I’ve been very fortunate in my career to serve in positions that were not held by Filipino Americans. I believe I was the only Filipino American attorney in the two large law firms in which I worked before joining the U.S. Attorney’s Office. I soon learned after joining the U.S. Attorney’s Office that I was again the only Filipino American prosecutor in the criminal division, and when I left in 2014, I was still the only Filipino American among over 200 lawyers. The bench suffers from a similar lack of diversity. Even though Filipino Americans are the largest Asian minority group in California, of approximately 1655 Superior Court judges, there are only 11 Filipino American judges. Similarly, out of 603 federal district judge positions in the United States, there is only one Filipino American. Last year, the Superior Court held a diversity summit to attract more minorities to the bench. The Asian bar associations have recently come together to build a judicial pipeline designed to recruit qualified Asian-American lawyers for the bench and provide mentorship and guidance during the judicial application process.

AALM: In closing, please tell us a story from your days on the bench.

Villeza: Once I was detained by law enforcement in our own courthouse. During the afternoon recess at Metro, I went downstairs to mail a few letters at the box near the elevators on the first floor, close to the courthouse front entrance. A suspicious court security officer, who didn’t recognize me, stopped and asked for my identification. After six months on the bench at Metro, it didn’t occur to me that I needed my ID to mail some letters inside the courthouse. So I identified myself as the judge in Department 70, but the officer, unconvinced, called for backup. I was detained in the lobby, among onlookers who were waiting to catch the elevators, some of whom were probably on their way to my courtroom. Eventually, they let me go. They were probably a bit embarrassed when they came into my courtroom to see me on the bench. Since then, I carry my ID at all times.

“As a judge, I feel I’ve been able to make a difference by serving the victims of street crime or by helping those with a drug or alcohol problem in need of counseling.”