For a soldier in combat, preparation can make the difference between victory and defeat.

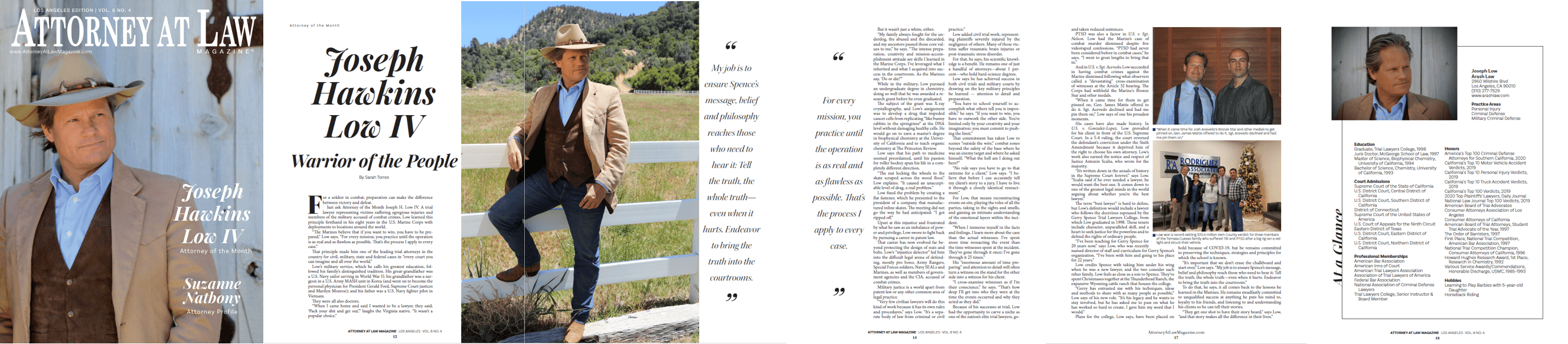

Just ask Attorney of the Month Joseph Hawkins Low IV. A trial lawyer representing victims suffering egregious injuries and members of the military accused of combat crimes, Low learned this principle firsthand in his eight years in the U.S. Marine Corps with deployments to locations around the world.

“The Marines believe that if you want to win, you have to be prepared,” Low says. “For every mission, you practice until the operation is as real and as flawless as possible. That’s the process I apply to every case.”

That principle made him one of the leading trial attorneys in the country for civil, military, state and federal cases in “every court you can imagine and all over the world.”

Low’s military service, which he calls his greatest education, followed his family’s distinguished tradition. His great-grandfather was a U.S. Navy sailor serving in World War II; his grandfather was a surgeon in a U.S. Army MASH unit in Korea (and went on to become the personal physician for President Gerald Ford, Supreme Court justices and Marilyn Monroe); and his father was a U.S. Navy fighter pilot in Vietnam.

They were all also doctors.

“When I came home and said I wanted to be a lawyer, they said, ‘Pack your shit and get out,’” laughs the Virginia native. “It wasn’t a popular choice.”

But it wasn’t just a whim, either.

“My family always fought for the underdog, the abused and the discarded, and my ancestors passed those core values to me,” he says. “The intense preparation, creativity and mission-accomplishment attitude are skills I learned in the Marine Corps. I’ve leveraged what I inherited and what I acquired into success in the courtroom. As the Marines say, ‘Do or die!’”

While in the military, Low pursued an undergraduate degree in chemistry, doing so well that he was awarded a research grant before he even graduated.

The subject of the grant was X-ray crystallography, and Low’s assignment was to develop a drug that impeded cancer cells from replicating “like bunny rabbits in the springtime” at the DNA level without damaging healthy cells. He would go on to earn a master’s degree in biophysical chemistry at the University of California and to teach organic chemistry at The Princeton Review.

Low says that his path to medicine seemed preordained, until his passion for roller hockey spun his life in a completely different direction.

“The nut locking the wheels to the skate scraped across the wood floor,” Low explains. “It caused an unacceptable level of drag, a real problem.”

Low fixed the problem by creating a flat fastener, which he presented to the president of a company that manufactured inline skates. The meeting did not go the way he had anticipated: “I got ripped off.”

Upset at this injustice and frustrated by what he saw as an imbalance of power and privilege, Low swore to fight back by pursuing a career in patent law.

That career has now evolved far beyond protecting the design of nuts and bolts. Low’s “injustice detector” led him into the difficult legal arena of defending, mostly pro bono, Army Rangers, Special Forces soldiers, Navy SEALs and Marines, as well as members of government agencies and the CIA, accused of combat crimes.

Military justice is a world apart from patent law or any other common area of legal practice.

“Very few civilian lawyers will do this kind of work because it has its own rules and procedures,” says Low. “It’s a separate body of law from criminal or civil practice.”

Low added civil trial work, representing plaintiffs severely injured by the negligence of others. Many of those victims suffer traumatic brain injuries or post-traumatic stress disorder.

For that, he says, his scientific knowledge is a benefit. He remains one of just a handful of attorneys—about 1 percent—who hold hard-science degrees.

Low says he has achieved success in both civil trials and military courts by drawing on the key military principles he learned — attention to detail and preparation.

“You have to school yourself to accomplish what others tell you is impossible,” he says. “If you want to win, you have to outwork the other side. You’re limited only by your creativity and your imagination; you must commit to pushing the limit.”

That commitment has taken Low to scenes “outside the wire,” combat zones beyond the safety of the base where he was an enemy target and where he asked himself, “What the hell am I doing out here?”

“No rule says you have to go to that extreme for a client,” Low says. “I believe that before I can accurately tell my client’s story to a jury, I have to live it through a closely identical reenactment.”

For Low, that means reconstructing events on site, playing the roles of all the parties, taking in the sights and smells, and gaining an intimate understanding of the emotional layers within the incident.

“When I immerse myself in the facts and feelings, I learn more about the case than the actual witnesses. I’ve spent more time reenacting the event than the time witnesses spent at the incident. They’ve gone through it once; I’ve gone through it 25 times.”

His “enormous amount of time preparing” and attention to detail will often turn a witness on the stand for the other side into a witness for his client.

“I cross-examine witnesses as if I’m their conscience,” he says. “That’s how deep I’ll get into who they were at the time the events occurred and why they acted as they did.”

Because of his successes at trial, Low had the opportunity to carve a niche as one of the nation’s elite trial lawyers, going where others fear to tread, he says. He is one of the fewer than 5 percent of U.S. attorneys with trial experience, and he frequently answers the call to step in for other lawyers to present their clients’ cases in court.

“Going to trial is when I can make a real difference,” he says. “Typically, another lawyer will call me on a difficult case with the potential for a large monetary verdict. If the lawyer believes he can’t get the kind of numbers I can get, he wants me to conduct the trial.”

One such case was Cuevas v. Rai Transport. In December 2019, Low won a $70.5 million jury verdict, the largest personal injury verdict ever in Kern County. A tractor-trailer driven by the defendant’s employee struck Tomasa Cuevas’ vehicle. Tomasa and her son, Alejandro, suffered brain injuries. Her daughter, Maritza, was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Rai’s insurance carrier disputed allegations that the big rig driver ran a red light, believing no evidence existed to prove he was at fault. Pre-trial investigation, however, uncovered a surveillance video that showed the driver’s failure to obey the traffic signal. Low’s team also discovered the driver had a suspended license and 14 other driving violations. After a 12-day trial, the jury reached the record verdict, which included $5.5 million for Maritza, a record amount for PTSD. The verdict is the No. 1 vehicle injury verdict in California in 2019, No. 5 overall, and No. 35 on the nationwide list.

In Carter v. Kern High School District, a student in a mascot costume was attacked at a sporting event at a rival school. No one believed the plaintiff could win the case. Despite the odds, Low delivered a $10.5 million verdict, which at the time was the largest verdict in Kern County history. The 2016 win, now widely recognized as “the chicken suit case,” has become a teaching tool for other trial lawyers.

In addition to Cuevas, Low pulled off two other unexpected civil verdicts in 2019.

In McPhoy v. Ramirez, Low convinced a Santa Monica jury to award slightly more than $11 million to a 70-year-old plaintiff who suffered brain injuries after being T-boned by a speeding driver. In closing, Low compared her life now to before the wreck.

McPhoy was healthy, fashion-conscious, family-oriented, extroverted, talkative and always happy. After the trauma, she became a woman of deformities, paranoia, debilities, and isolation. The court reporter told Low, “That was a really good closing, but I have been in this courthouse my entire career and juries here do not give that kind of money.” McPhoy was the 38th largest verdict in California in 2019.

In Bibbie v. A-Quality Transport, the jury awarded the 74-year-old auto accident plaintiff $3.3 million, all for pain and suffering. The defense disputed liability and offered$120,000 to settle before trial. After Low completed voir dire, the defense increased its offer to $375,000. After Low crossed-examined the defense’s chief expert, he countered with $450,000. The defense refused. This verdict was the largest ever in Riverside County for a cervical spine injury—10 times the going rate in the county, according to the defense—and the 89th top verdict in California for 2019.

Speaking to Low’s creativity and talents, several of his military cases have been groundbreaking.

In U.S. v. Cpl. Magincalda, Low was the first attorney to introduce post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury as defenses for capital murder in a U.S. military war crime trial. One of the media-dubbed “Pendleton 8,” Low’s Marine Corps client, who could have received the death penalty, was acquitted, allowed to return to active duty and awarded a third Purple Heart even though other members of the group had already pleaded guilty and taken reduced sentences.

PTSD was also a factor in U.S. v. Sgt. Nelson. Low had the Marine’s case of combat murder dismissed despite five videotaped confessions. “PTSD had never been considered before in combat cases,” he says. “I went to great lengths to bring that in.”

And in U.S. v. Sgt. Acevedo, Low succeeded in having combat crimes against the Marine dismissed following what observers called a “devastating” cross-examination of witnesses at the Article 32 hearing. The Corps had withheld the Marine’s Bronze Star and other medals.

“When it came time for them to get pinned on, Gen. James Mattis offered to do it. Sgt. Acevedo declined and had me pin them on,” Low says of one his proudest moments.

His cases have also made history. In U.S. v. Gonzalez-Lopez, Low prevailed for his client in front of the U.S. Supreme Court. In a 5-4 ruling, the court reversed the defendant’s conviction under the Sixth Amendment because it deprived him of the right to choose his own attorney. Low’s work also earned the notice and respect of Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote for the majority.

“It’s written down in the annals of history in the Supreme Court forever,” says Low. “Scalia said if he ever needed a lawyer, he would want the best one. It comes down to one of the greatest legal minds in the world arguing about whether you’re the best lawyer.”

The term “best lawyer” is hard to define, but Low’s definition would include a lawyer who follows the doctrines espoused by the Gerry Spence Trial Lawyers College, from which Low graduated in 1998. Those tenets include character, unparalleled skill, and a heart to seek justice for the powerless and to defend the rights of ordinary people.

“I’ve been teaching for Gerry Spence for 20 years now,” says Low, who was recently named director of staff and curriculum for Gerry Spence’s organization. “I’ve been with him and going to his place for 22 years.”

Low credits Spence with taking him under his wing when he was a new lawyer, and the two consider each other family. Low feels as close as a son to Spence. They’ve spent Christmases together at the Thunderhead Ranch, the expansive Wyoming cattle ranch that houses the college.

“Gerry has entrusted me with his techniques, ideas and methods to share with as many people as possible,” Low says of his new role. “It’s his legacy and he wants to stay involved, but he has asked me to pass on what he has worked so hard to create. I gave him my word that I would.”

Plans for the college, Low says, have been placed on hold because of COVID-19, but he remains committed to preserving the techniques, strategies and principles for which the school is known.

“It’s important that we don’t erase the chalkboard and start over,” Low says. “My job is to ensure Spence’s message, belief and philosophy reach those who need to hear it: Tell the truth, the whole truth—even when it hurts. Endeavor to bring the truth into the courtroom.”

To do that, he says, it all comes back to the lessons he learned in the Marines. He remains steadfastly committed to unqualified success at anything he puts his mind to, loyalty to his friends, and listening to and understanding his clients so he can tell their stories.

“They get one shot to have their story heard,” says Low, “and that story makes all the difference in their lives.”