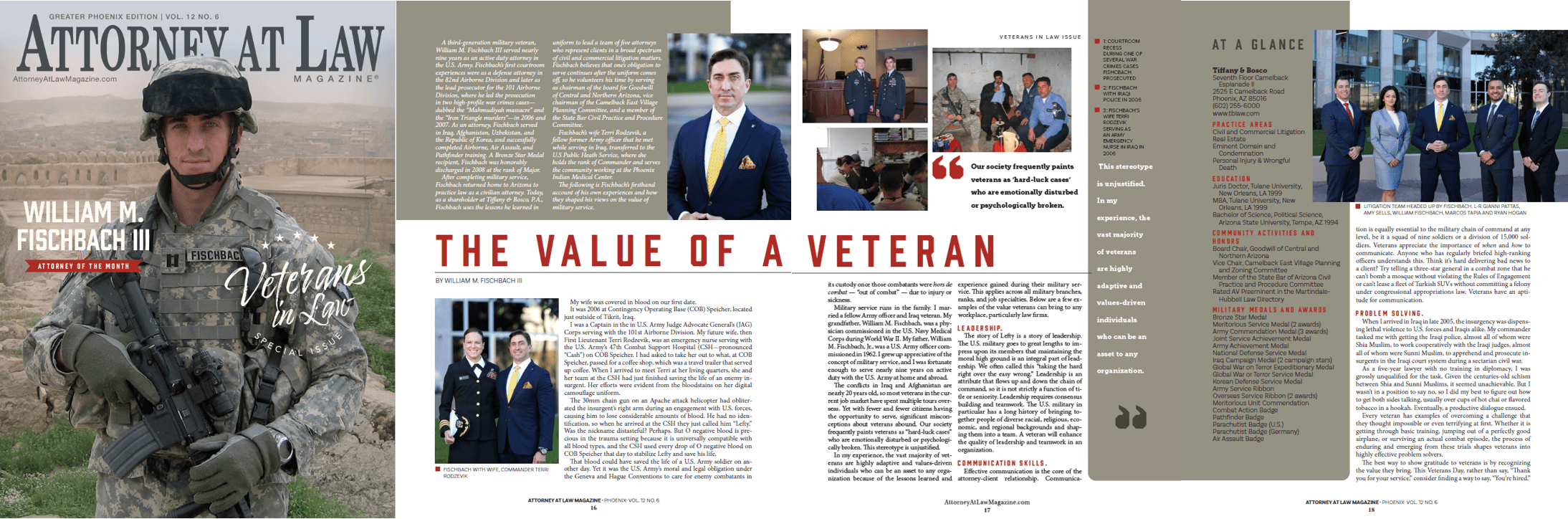

A third-generation military veteran, William M. Fischbach III served nearly nine years as an active duty attorney in the U.S. Army. Fischbach’s first courtroom experiences were as a defense attorney in the 82nd Airborne Division and later as the lead prosecutor for the 101 Airborne Division, where he led the prosecution in two high-profile war crimes cases—dubbed the “Mahmudiyah massacre” and the “Iron Triangle murders”—in 2006 and 2007. As an attorney, Fischbach served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and the Republic of Korea, and successfully completed Airborne, Air Assault, and Pathfinder training. A Bronze Star Medal recipient, Fischbach was honorably discharged in 2008 at the rank of Major.

After completing military service, Fischbach returned home to Arizona to practice law as a civilian attorney. Today, as a shareholder at Tiffany & Bosco, P.A., Fischbach uses the lessons he learned in uniform to lead a team of five attorneys who represent clients in a broad spectrum of civil and commercial litigation matters. Fischbach believes that one’s obligation to serve continues after the uniform comes off, so he volunteers his time by serving as chairman of the board for Goodwill of Central and Northern Arizona, vice chairman of the Camelback East Village Planning Committee, and a member of the State Bar Civil Practice and Procedure Committee.

Fischbach’s wife Terri Rodzevik, a fellow former Army officer that he met while serving in Iraq, transferred to the U.S Public Heath Service, where she holds the rank of Commander and serves the community working at the Phoenix Indian Medical Center.

The following is Fischbach’s firsthand account of his own experiences and how they shaped his views on the value of military service.

My wife was covered in blood on our first date.

It was 2006 at Contingency Operating Base (COB) Speicher, located just outside of Tikrit, Iraq.

I was a Captain in the in U.S. Army Judge Advocate General’s (JAG) Corps serving with the 101st Airborne Division. My future wife, then First Lieutenant Terri Rodzevik, was an emergency nurse serving with the U.S. Army’s 47th Combat Support Hospital (CSH—pronounced “Cash”) on COB Speicher. I had asked to take her out to what, at COB Speicher, passed for a coffee shop, which was a travel trailer that served up coffee. When I arrived to meet Terri at her living quarters, she and her team at the CSH had just finished saving the life of an enemy insurgent. Her efforts were evident from the bloodstains on her digital camouflage uniform.

The 30mm chain gun on an Apache attack helicopter had obliterated the insurgent’s right arm during an engagement with U.S. forces, causing him to lose considerable amounts of blood. He had no identification, so when he arrived at the CSH they just called him “Lefty.” Was the nickname distasteful? Perhaps. But O negative blood is precious in the trauma setting because it is universally compatible with all blood types, and the CSH used every drop of O negative blood on COB Speicher that day to stabilize Lefty and save his life.

That blood could have saved the life of a U.S. Army soldier on another day. Yet it was the U.S. Army’s moral and legal obligation under the Geneva and Hague Conventions to care for enemy combatants in its custody once those combatants were hors de combat — “out of combat” — due to injury or sickness.

Military service runs in the family. I married a fellow Army officer and Iraq veteran. My grandfather, William M. Fischbach, was a physician commissioned in the U.S. Navy Medical Corps during World War II. My father, William M. Fischbach, Jr., was a U.S. Army officer commissioned in 1962. I grew up appreciative of the concept of military service, and I was fortunate enough to serve nearly nine years on active duty with the U.S. Army at home and abroad.

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan are nearly 20 years old, so most veterans in the current job market have spent multiple tours overseas. Yet with fewer and fewer citizens having the opportunity to serve, significant misconceptions about veterans abound. Our society frequently paints veterans as “hard-luck cases” who are emotionally disturbed or psychologically broken. This stereotype is unjustified.

In my experience, the vast majority of veterans are highly adaptive and values-driven individuals who can be an asset to any organization because of the lessons learned and experience gained during their military service. This applies across all military branches, ranks, and job specialties. Below are a few examples of the value veterans can bring to any workplace, particularly law firms.

Leadership.

The story of Lefty is a story of leadership. The U.S. military goes to great lengths to impress upon its members that maintaining the moral high ground is an integral part of leadership. We often called this “taking the hard right over the easy wrong.” Leadership is an attribute that flows up and down the chain of command, so it is not strictly a function of title or seniority. Leadership requires consensus building and teamwork. The U.S. military in particular has a long history of bringing together people of diverse racial, religious, economic, and regional backgrounds and shaping them into a team. A veteran will enhance the quality of leadership and teamwork in an organization.

Communication skills.

Effective communication is the core of the attorney-client relationship. Communication is equally essential to the military chain of command at any level, be it a squad of nine soldiers or a division of 15,000 soldiers. Veterans appreciate the importance of when and how to communicate. Anyone who has regularly briefed high-ranking officers understands this. Think it’s hard delivering bad news to a client? Try telling a three-star general in a combat zone that he can’t bomb a mosque without violating the Rules of Engagement or can’t lease a fleet of Turkish SUVs without committing a felony under congressional appropriations law. Veterans have an aptitude for communication.

Problem solving.

When I arrived in Iraq in late 2005, the insurgency was dispensing lethal violence to U.S. forces and Iraqis alike. My commander tasked me with getting the Iraqi police, almost all of whom were Shia Muslim, to work cooperatively with the Iraqi judges, almost all of whom were Sunni Muslim, to apprehend and prosecute insurgents in the Iraqi court system during a sectarian civil war.

As a five-year lawyer with no training in diplomacy, I was grossly unqualified for the task. Given the centuries-old schism between Shia and Sunni Muslims, it seemed unachievable. But I wasn’t in a position to say no, so I did my best to figure out how to get both sides talking, usually over cups of hot chai or flavored tobacco in a hookah. Eventually, a productive dialogue ensued.

Every veteran has examples of overcoming a challenge that they thought impossible or even terrifying at first. Whether it is getting through basic training, jumping out of a perfectly good airplane, or surviving an actual combat episode, the process of enduring and emerging from these trials shapes veterans into highly effective problem solvers.

The best way to show gratitude to veterans is by recognizing the value they bring. This Veterans Day, rather than say, “Thank you for your service,” consider finding a way to say, “You’re hired.”