The Covid-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on North Carolina’s civil justice system. It’s affected attorneys but also forensic economists like me, who work for attorneys on civil lawsuits. The pandemic has delayed trials and caused back-ups throughout the court system. It has also altered the economy that we forensic economists analyze to produce our expert reports.

My first indication that Covid was affecting the legal world was a news article last spring that cited data from the North Carolina Judicial Branch (NCJB). From early March to mid-April of 2020, weekly civil filings in the state fell 70 percent. That was huge, and months later, I assumed that it explained a temporary drop in my caseload in early 2021.

CIVIL FILINGS DOWN 22%

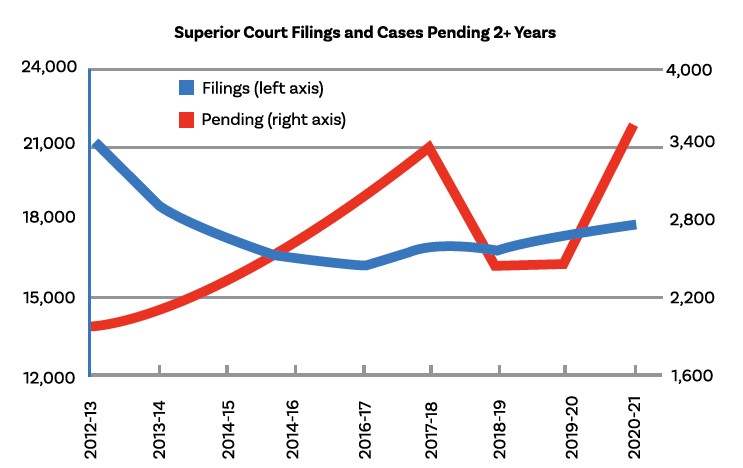

However, a closer look at NCJB data tells a more complicated story. From FY 2018-19 to 2020-21, annual civil filings fell 22 percent. But in Superior Courts, where bigger lawsuits are filed and where we forensic economists generally appear, civil filings actually rose slightly over the same two-year period.

The drop in civil filings was almost entirely due to a 54 percent decline in civil filings before magistrates, who try such civil cases as landlord evictions and small claims. In FY 2018-19, magistrates handled 40 percent of all civil filings in the state.

The pandemic didn’t discourage attorneys from filing lawsuits in Superior Court, but once filed, cases took longer to be resolved. At the end of FY 2020-21, there were 3,561 cases in Superior Courts that were two or more years old, which was 45 percent more than the year before. The median age of pending cases was 295 days, also up sharply over previous years.

The case backlog in the NC court system has finally begun to clear, and my caseload has recovered nicely. Assuming that we won’t revert to the lockdowns of 2020, what remains for forensic economists like me is to determine how a pandemic lasting 18 months (and counting!) will affect our economic projections, whether of lost earnings or lost profits. For example, the pandemic has suppressed interest rates, which we use to calculate present values. Lower interest rates imply larger damages calculations, because low rates cause lump-sum awards and settlements to appreciate more slowly in the future.

ECONOMY-WIDE EFFECTS

Recent data on wage and price inflation, which often figure into our analyses, are mixed. The numbers go in different directions in different categories. The same is true for labor-market data. Initially, employment fell sharply, but the effects weren’t uniform through the economy and government programs replaced many people’s lost income.

If these data movements are temporary, the effect on forensic economics will be minimal. And yet the economy won’t completely return to normal. Business experts predict that some adjustments to the pandemic, such as working from home, will become permanent features of economic life for many workers. Office space may become less valuable for your corporate clients and perhaps your own firm. But will any permanent changes leak into the data I rely upon as an economist?

These are real issues, and yet my reaction is: “So what else is new?” The economy is always in flux; data are always rising and falling. This time it’s a pandemic. A decade ago, it was the deepest recession since the 1930s. It’s always something! No matter what, I’ll be out there, making sense of the data just as I did before anyone had ever heard of Covid-19.