By now we have all heard about the gender pay gap – the difference in earnings between men and women. Data from the 2018 U.S. Census Bureau shows that women average just 82 cents for every $1 earned by men based on full-time year-round work, and numbers have generally been much bleaker for women of color.

- Black women make 62 cents on the dollar.

- Hispanic women make 54 cents on the dollar.

- Asian women make 89 cents on the dollar.

- Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander women make 61 cents on the dollar.

- American Indian or Alaskan Native women make 57 cents on the dollar.

Lawyers are no exception. For several years, women have made up roughly half the graduating law school classes. Yet, women are a minority of high-level partners in firms, and generally under-represented in private practice. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in 2019 women lawyers made on average $1,878 per week whereas male lawyers made $2,202; meaning women attorneys made 85 cents per $1 of their male counterparts. Why is this happening? We look at three common myths to provide deeper explanations and offer practical solutions.

Myth #1: Lack of Talent in the Pipeline will be Resolved as Women Entering the Profession Rise Through the Ranks

The truth is that women have been entering the profession in near equal numbers to men for decades and yet have never reached similar parity in compensation.

According to a Jurist article, for the last 34 years the percentage of men and women who attend law school hasn’t been separated by more than 10%. And 50% or more of law school classes have been composed of women since 2016. This holds true at the nation’s top law schools— dispelling the myth of a lack of top tier female talent. And in an ABA Journal article, it’s revealed that eight of the Top 10 ranked law schools reported 1L classes for 2020 that were between 48% women (Yale) and 66% women (UC Berkeley). Women also hold about half of summer associate positions, according to the NALP.

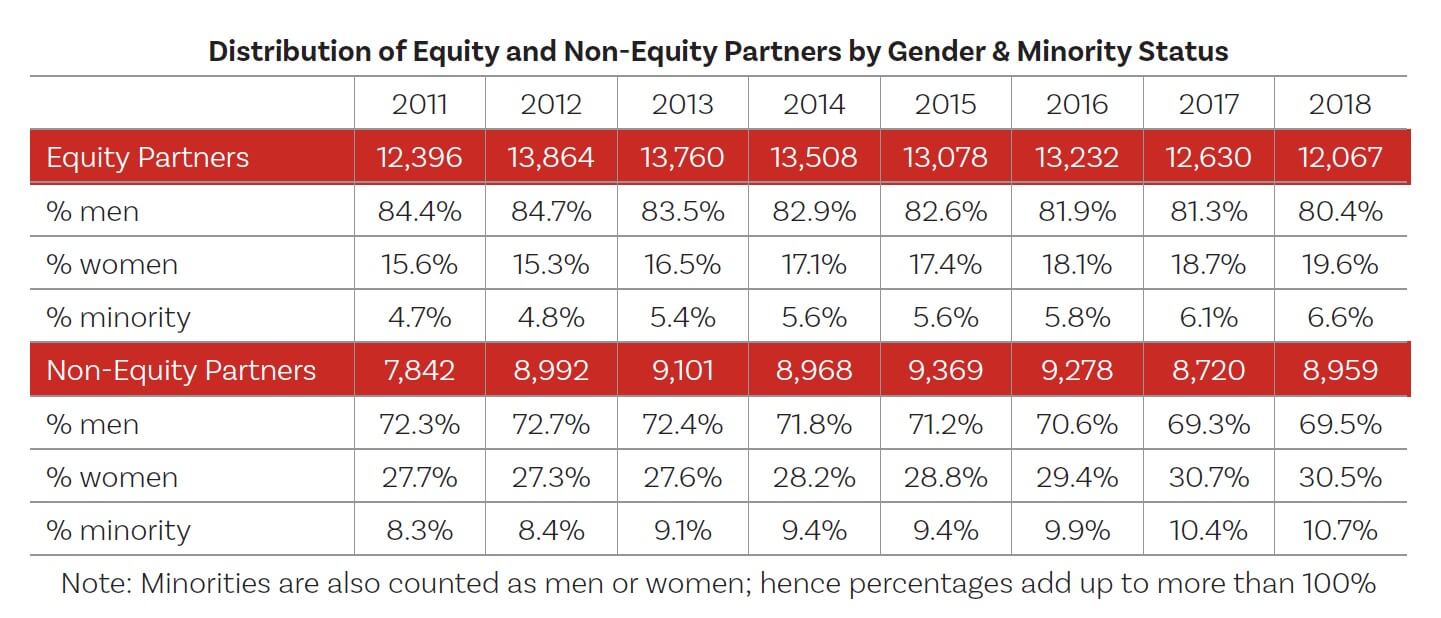

Despite equal numbers entering the profession, according to the American Bar, women make up only 20% of equity partners and women of color comprise less than 2% of equity partners.

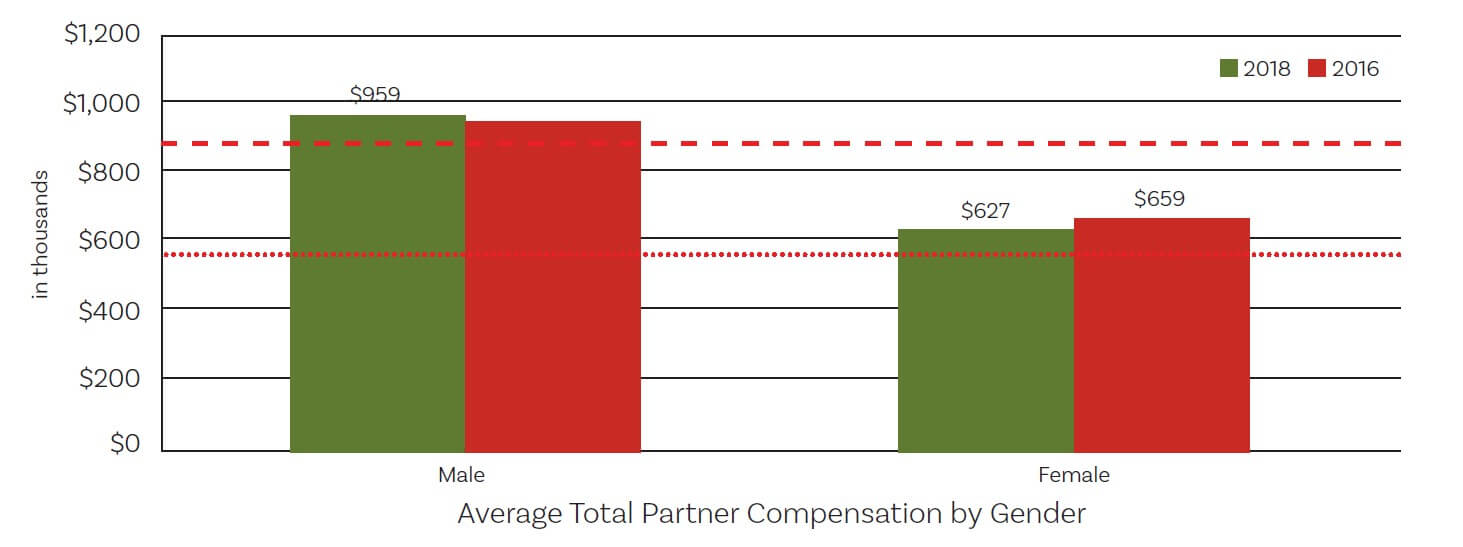

These figures have changed little over the last decade. According to an American Bar article, the high barrier for women entering the equity partner ranks has a direct impact on women’s compensation. As women get deeper into their careers, and time has passed, the wage gap widens rather than narrows. A recent study by legal recruiters Major, Lindsey & Africa found a 53% difference in average pay between male and female partners across large U.S. law firms. And, rather than correcting over time, the pay gap for partners has widened since 2016.

For women lawyers of color, all these numbers are worse— leading a significant majority to leave the profession altogether.

So, if time is not the answer, what is? Two key components for narrowing the promotion, and therefore wage, gap are the active sponsorship of women lawyers by someone on the “inside” who advocates for and promotes their visibility among firm leadership, and the reduction of biases in decision-making through training, transparency and inclusion.

The ABA Task Force on Gender Equity has identified 12 practices to promote gender equity in law firm compensation. The ABA’s recommendations focus on assessing, reporting, and targeting gender disparities that impact compensation by developing formal, transparent processes to drive accountability and change. Among the recommended practices are systems to promote fair and accurate allocation of billing and origination credit, developing a process to resolve allocation disputes, requiring and tracking of diversity in pitch teams, and implementing formal client succession protocols.

Another critical practice is rewarding behaviors that promote institutional sustainability and not simply individual rainmaking, including internally focused activities related to talent development and retention, committee participation, and leadership in the firm’s strategic initiatives, and externally focused activities like writing, speaking, pro bono engagement, and bar association leadership. Too often women are asked to participate in activities that are not recognized in the compensation process, whereas their male colleagues avoid to some extent participation in such activities.

Myth #2: Women Aren’t Asking for More Money

For any employee, according to Ben Le Fort, their starting salary at their first job serves as an anchor throughout the rest of their career. Many people believe that women make less because they don’t ask for more money, for a promotion or for a raise. The truth, according to The Atlantic, is that women are negotiating and asking for raises and promotions just as much as men, but they are not being rewarded for it. A 2007 study found that male employers are less likely to hire a woman who negotiates salary – deeming them “demanding.” Understandably, this can make women reluctant to negotiate.

This is not an individual women’s fault, and individual women are not to blame for the pay gap because they are not asking for more money. However, until the culture changes, women can and should take charge of negotiating.

Strategies to Help Women Succeed at Negotiation

No. 1: Ask “how flexible is that” when offered a salary or a raise. After all, according to the Harvard Business Review, negotiating may make your employer respect you more, not less—attorneys are expected to negotiate on behalf of their clients, so why shouldn’t you negotiate on your own behalf?

No. 2: Try negotiating more than one thing at a time—salary and vacation days, for example—to make compromise more likely, according to the Harvard Business Review.

No. 3: Use your network to research ahead of time what is a reasonable ask. Women often undervalue themselves, so they often do not ask for as much as a male candidate might. Negotiation experts say that if your first request is accepted, then you were not asking for enough in the first place.

Closing the Gender Pay Gap Locally

Additionally, a number of practices can be implemented at a firm-level, local level, and state level to close the gender pay gap at the salary negotiation phase:

No. 1: Implement a policy banning questions about salary history when determining what salary a new employee will be offered. Price the job and skills, not prior inequities and stereotypes. There is a current bill proposed in Minnesota, HF 4100, that would do just that.

No. 2: Increase transparency around compensation. A 2013 report by the American Bar Association recommended that firms put all factors on which compensation decisions are made in writing and communicate them to all partners. This would encourage compensation committees to stick to the articulated principles and allow partners to understand how compensation decisions are made.

No. 3: Make it clear when something is negotiable. A 2014 study, found that when there was no explicit statement on a job application that wages were negotiable, male applicants were more likely to negotiate than women. However, when the job description explicitly mentioned that wages were negotiable, both genders were equally likely to initiate negotiations and equally hesitant to offer working for lower wages than posted.

Myth #3: Women Tend to Take More Time Off and be Less Committed after Having Children

Men’s and women’s careers tend to evolve similarly until the birth of the first child; after the birth, those career trajectories never match up again. Research in multiple studies demonstrates a 5% wage penalty per child for women and an average career wage penalty of about 20% (factoring in all caretaking responsibilities). Many studies have focused on this causation, called the “caregiver penalty” or the “motherhood penalty.”

Many attorneys excuse away the caregiver penalty within our own profession: women take time off for maternity leaves; women do less after-hours marketing after they have children; women spend less time working and billing; women are more likely to work part-time.

Despite these anecdotal explanations of women attorneys investing fewer hours into their practice, “many years of NAWL (National Association of Women Lawyers) data have shown that there are no significant differences between the hours recorded by men and women attorneys at different levels and in different roles.” This is true for both billable and total hours recorded. While we lack specific, long-term data regarding reduced hours for parenthood within the legal profession, we do know that for American women as a whole, reduced hours, lost experience, and related decisions account for only one-third of the caregiver penalty.

And for the other two-thirds? There is an incorrect perception that women attorneys are less committed to practice after having children. While women earn less because of having children, a University of Massachusetts study from 2010 demonstrates that fathers earn 11% more than non-fathers. Men who have children are seen as more dedicated to their jobs because they have a family to provide for, while women who have children are seen as less dedicated to their jobs because they are distracted by family responsibilities. Women receive the caregiver penalty; men receive the fatherhood bonus.

When perceived to be less competent and invested in their careers, women attorneys are also disproportionately punished for their errors. Numerous studies have shown that women and BIPOC are much more likely to be penalized for marginal mistakes; as one author pointed out, “many of the women I spoke with felt that they were unable to recover from marginal errors that were often deemed fatal to their advancement.” Our concern is not just that there are far fewer women partners than men partners—it is that a huge proportion of the women associates leave these firms altogether.

Consider also the attorneys in power. According to NAWL’s 2018 Survey Report, women make up only 25% of firm governance roles, 22% of firm-wide managing partners, 20% of office-level managing partners, and 22% of practice group leaders. These numbers are far more dismal when considering other marginalized attorneys – women attorneys of color, women attorneys with disabilities, and women who identify as LGBT+. Women and other marginalized attorneys are underrepresented at the table where decisions are made about their long-term career prospects.

Women attorneys are systematically unsupported and un-sponsored, held to a higher standard, and face routine bias as mothers and caregivers. For firms and legal departments, the options to overcome and prevent these implicit biases are numerous – include more women and marginalized attorneys in promotion and compensation decisions; have bias interruption interventions throughout the course of an attorney’s career trajectory; update the compensation and credit sharing mechanisms; and take other steps, such as client succession planning, that make the hiring, promotion, and compensation of women and marginalized attorneys a realistic business goal tied to specific, financial objectives.

The Global Pandemic-Sized Elephant

We cannot talk today about the pay gap without also addressing today’s global pandemic. In the “before times”—the days and weeks before the coronavirus began spreading in earnest in the United States and the lives of millions of Americans were inexorably changed—women’s participation in the U.S. labor market hit an historic milestone: a December 2019 Labor Department jobs report revealed that women held more U.S. jobs than men for the first time in nearly a decade. Within weeks of nationwide COVID-19-related shutdowns, the happy news of women’s labor-market gains vanished. In its place were dire reports about the pandemic’s anticipated negative impact on the work opportunities and earning potential of women, especially BIPOC women, for years to come.

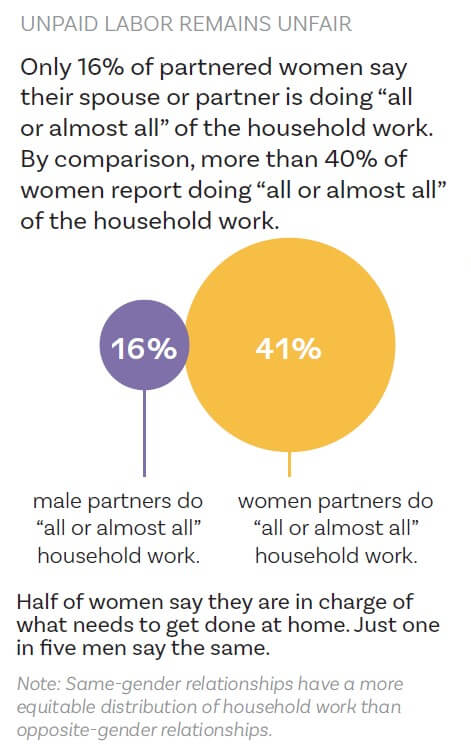

Experts studying the outsized impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on women observed that two independent forces appear to be at play. First, reports on women’s increased participation in the labor market pre-COVID were largely explained by growth in service-industry jobs that are disproportionately held by women—and disproportionately subject to disruption by COVID-related shutdowns. Second, the fact that women have long been responsible for a disproportionate share of childcare and housework duties in even dual-income families has only worsened with the widespread closure of schools and daycares and the sudden unavailability of  supportive services, like housecleaners. There are many intersecting reasons for this phenomenon, most of which relate to preexisting gender-inequality issues. The pandemic has, in some ways, exposed the real reasons why the pay gap exists.

supportive services, like housecleaners. There are many intersecting reasons for this phenomenon, most of which relate to preexisting gender-inequality issues. The pandemic has, in some ways, exposed the real reasons why the pay gap exists.

Surveys of female lawyers have revealed that widespread increases in home and childcare responsibilities have not been offset by reductions in professional workload, as expectations related to productivity and billable-hours requirements remain unchanged. The untenable result is that, for many professional women, working from home is a 24/7 proposition. Small wonder, then, that the pandemic has also resulted in an “observed increase in the gender gap in mental health.” Moreover, the fact that many women simply can’t keep up with the competing demands of their jobs and families has experts predicting that the pandemic will “scar a generation of working mothers” and roll back the limited gains in workplace and pay equality that have been achieved in recent decades.

At the company level, it is critical that employers use hard data to make decisions about compensation, promotions, furloughs, and work assignments to ensure that implicit bias is not seeping into decision-making processes. Moreover, workplace leaders must model diversity, inclusion, and flexibility in their words and actions to ensure that the historically underrepresented groups who are bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s effects are not forced out of the workplace. Most importantly, systemic changes are needed at the state and local government level to ensure that families are appropriately supported, and caregiving is appropriately valued as an important social service, not a professional liability.

The pandemic is undoubtedly going to intensify the pay gap problem, so it is more important now than ever to take note and make change. Solutions must be intentional and multifaceted to address pervasive bias and the systemic roots of the gender pay gap in law firm and legal department reward structures.

The Pay Equity Initiative is a sub-committee to Minnesota Women Lawyers’ (MWL) Equity Committee. The Initiative seeks to promote and advocate for equal pay for women and diverse/under-represented attorneys. This includes pay equity for similarly situated positions, as well as the promotion and retention of women and diverse/under-represented attorneys to higher levels of leadership and responsibility within their organizations. For more information about the Initiative, our ongoing actions, or resources about pay equity, visit the MWL website at: https://mwlawyers.org/ and look for Pay Equity under Initiatives.

Furthermore, MWL recognizes that this Initiative will best find success if it represents the whole of our legal community. As stated in the organization’s Diversity and Inclusion Statement “MWL believes that bringing diverse individuals together allows us to collectively and more effectively develop ideas, respond to the needs of our membership, and address issues within our legal community.” To that end, MWL invites and welcomes attorneys who represent the diversity of the profession to join us in this critical work. To get involved, contact Initiative Chair Kelly Clark at [email protected].

The following members contributed to this piece: Christine B. Courtney is the principal attorney of Courtney Law Office, where she practices primarily in estate and incapacity planning, trust and probate administration and elder law. E. Meaghan Clayton is an employment litigator at Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP. Kelly K. Clark is an immigration attorney at Heinz Law PLLC. Virginia R. McCalmont is an attorney at Greene Espel PLLP. Meredith Gingold is a 3L at the University of Minnesota Law School and a former Pay Equity Intern for Minnesota Women Lawyers.

Sponsored by Shepherd Data Services.