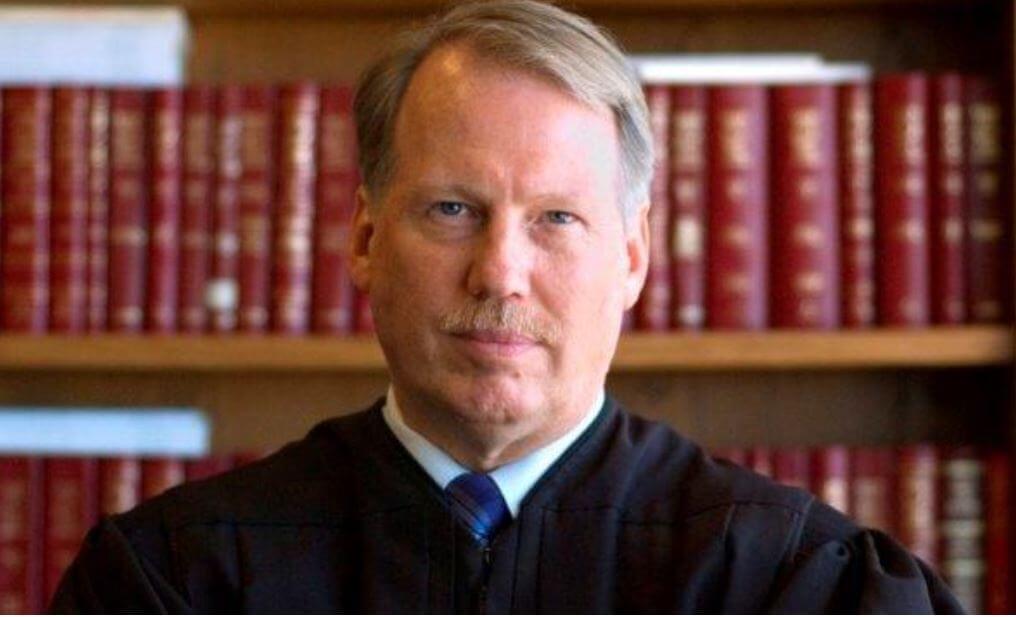

Kathy Rosner, a Longtime Cuyahoga County Housing Court Specialist discusses the life and career of Judge Raymond L. Pianka.

Judge Raymond L. Pianka, who passed away February 2017, was the consummate public servant. He never called in sick; he arrived early and stayed late; and he attended community meetings as oft en as two-three times a week. He was passionate about Cleveland and its neighborhoods and sought to preserve the city’s heritage, housing stock and neighborhoods as the director of a neighborhood development corporation, as a councilperson and as a judge. He knew every neighborhood, and virtually every street, in the city because he walked them and visited them frequently.

He chose to run for judge of the Cleveland housing court because he saw the potential for the court to be a tool for housing and neighborhood preservation. His idea of justice was not that of a judge sitting in the courtroom dispensing fines. His idea of justice was having housing court specialists “work miracles” by working with defendants to get properties repaired or transitioned to an owner who could repair and maintain the property. He repeatedly said from the bench that he wanted to see a defendant’s money go into the repair of the house, not the city’s general fund because the condition of the city’s housing stock and neighborhoods could do more to stabilize and improve the city than a few miscellaneous dollars.

“It can’t be done” was not an answer he accepted. He sought out solutions to every issue the court faced. When large property owners ignored the court by refusing to appear and failing to pay fines he revived the “clean hands doctrine.” The court would refuse to hear the eviction cases of landlords who did not appear on their criminal cases or pay their fines.

When the large banks and out-of-state property owners refused to appear before the court he resurrected “trials in absentia” hearing the cases and issuing judgments without them appearing. When the court of appeals said he could not do that, he started holding large corporate defendants in contempt of court for failing to appear and fining them daily. Fines were not allowed to go uncollected. Judge Pianka hired a law firm to do collections and fines were collected.

When working with the elderly, veterans and low-income defendants the judge made use of existing programs to get assistance the defendant might need, whether it was financial, housing, health care or food. He worked closely with the county land bank to assist property owners in getting properties that they did not want, and could not care for, out of their names.

From Mary Elliott, a Longtime Cuyahoga County Housing Court Specialist

Ray Pianka was a true public servant – caring deeply about the city’s people, and he served them, and all of their concerns he worked to help them into resolution – housing related or not.

He was a people person, always making himself accessible. He cared that issues people faced in the community affected their quality of life, so he gave residents direction – who to call, what to do, step-by-step processes to resolving that problem. Nothing in a city without a good economic base and all that goes along with poverty is resolved easily, but Ray Pianka only saw these challenges as a way to bring solutions, not reasons for what could not be done.

He collaborated with other like-minded city leaders, and did develop many innovative ways to address the deterioration of Cleveland’s housing stock. While the role of judge presiding over all things housing in Cleveland was a daunting task, he achieved success in getting compliance with the attitude of one property at a time. He wasn’t good at accepting the status quo; he pushed the envelope on getting things done – issues that other community leaders say are not do-able.

He was a fixer of problems

No was not in his vocabulary. He analyzed the issue, and found a way to create a solution, and expected his staffto do the same. In the years he presided over this court, he hired people that understood the city’s problems, and then fine-tuned his foot soldier’s skills to go into the community and give the constituents a road map for progress in their neighborhoods. Effectively, in many ways he cloned himself in his staff.

Housing stock represents the soul of the city, so when a family is evicted and their lives are left on the lawn, or a home is razed, part of the community’s soul is also stripped away. Homes are not just brick, mortar, plaster and lath, they’re the places where people’s lives are lived. Births, weddings, graduations, deaths – the culture of each street, each block, each community has emerged from these homes.

He also loved the architecture that was constructed in the early years of Cleveland. As a councilman, he worked to protect many of his ward’s historic structures, and made the city’s landmarks ordinances stronger in an effort to protect our past, and continued that work as a jurist, using local historians to write about important historic structures to bring awareness to the need to preserve these structures and our heritage.

He built a culture of hope for the disenfranchised that were not able to get city leaders to address the problems they faced, and so he instilled hope by meeting in the communities and through Power-point presentations with pictures of wonderful old structures that used to stand in Broadway, Miles, St. Clair, Detroit, Shoreway and across the city, and raised enthusiasm in those he met for what can be done now to bring these neighborhoods back to strong communities where you can live, work, raise children, grow old and be happy.