“We didn’t meet by accident,” declares a billboard for the Pirnia Law Group on my commute down Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. The city is awash with gigantic advertisements of this style, each hawking the services of local personal injury attorneys. At the office, newspaper headlines add to the day’s collage. A jury in Texas awards $352 million to a severely injured airline worker. Another in Iowa awards $97.4 million to a child and his family in a medical malpractice case.

According to recent reports, the post-pandemic era has ushered in some of the largest jury verdicts seen to date. Industry analysts warn us that nuclear verdicts are quickly becoming the norm, citing social inflation, generational shifts, and the coronavirus pandemic as causal factors. Although masks, large sums of money, and runaway juries make for an enticing read, I want to go back to those boulevard billboards. Most verdicts, after all, do not go nuclear. It’s the smaller claims, the routine personal injury cases, the ones that happen thousands of times a day, that have the largest impact on the litigation landscape. I want to know about those juries—the juries unimportant enough to notice.

Constructing Certainty

Most of the civil cases filed in the United States never reach a jury. The reason? Juries are considered to be the least predictable of the decision-makers in the legal system. This uncertainty (or the belief in this uncertainty) is used strategically. Attorneys deploy the threat of a jury trial to pressure their opposing counsel to drop or settle a case, often presenting high-low agreements as a tempting alternative to an unknown jury pool. Court mediators and trial judges are no exception, with both routinely cautioning parties against the unpredictability of juries.

But are jurors more unpredictable than judges? Maybe. Over the past 10 years, artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies have combed through millions of state trial court records, analyzing judicial rulings in ways that have rendered judicial decision-making processes more transparent and more predictable. Litigators are equipped with massive amounts of quantitative and qualitative information about individual judges, everything from their docket assignments to their party biases, their case durations, and their matter-type experiences. Perhaps, then, judicial decisions are more predictable because they have been made more predictable. Can the same happen for juries?

Integrating Verdict Data

Outcome prediction is an important part of practicing law. Clients expect their attorneys to provide them with accurate assessments of the potential consequences of any major legal decision. These assessments, which typically take place at the beginning of the litigation process, allow clients to strategize how they would like to navigate through a specific legal matter.

Litigators have always developed their own rudimentary tools for grappling with the unknown. In general, these tools assess the viability of a pending legal action by looking to the past. Litigators know that the details of past cases can provide invaluable insight into how they should position similar cases in the future. The problem is that this guidance has been impossible to access, especially for attorneys at the state trial court level. Thankfully, a market of legal analytics platforms have emerged to solve this problem, harnessing the rudimentary tools of litigators and expanding their capabilities with artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Companies like Trellis Research, Lex Machina, and Bloomberg Law have completely remapped the ways in which attorneys conduct legal research at the state trial court level. These platforms started by following the logics of conventional legal research. They equipped their users with the tools needed to conduct element-focused analyses of each asserted cause of action in a case. With access to a searchable database of prior decisional law, users could anticipate the processes their judge would need to follow in his or her assessment of a claim, breaking down a cause of action into its constituent elements and determining how the known facts of a case would need to be applied to each element.

While useful, this kind of analysis tells us little about how a jury might respond to a specific type of action. In recognition of this gap, legal analytics platforms have responded by integrating verdict data into their systems, amending their archives of case law, legal petitions, and judicial rulings to also include information related to case outcomes and settlement awards. This information is crucial, particularly for all those cases wherein judicial officers never issue formal opinions.

Slip and Falls

As one of the top causes of unintentional injuries, slip and falls can result in astronomical expenses, ranging from medical bills to lost wages. Every slip and fall case is unique. Some will settle at the onset of litigation. Some will make it all the way to trial. Others will settle days—maybe even hours—before trial begins. With verdict data, attorneys can begin to map the trajectories of different settlement strategies, identifying the range of possible outcomes for each and every decision along the way.

“[A] lot of cases are likely to settle because that’s the most common outcome,” explains Case Collard, a partner at Dorsey & Whitney.

But is this observation really true? And, if so, how true is it? With verdict analytics, it’s possible to unpack and verify the anecdotal claims litigators have been parlaying to their clients for decades.

We can, for example, pull a randomized sample of slip and fall cases filed against various municipalities in Los Angeles. Each entry contains a description of the case, the initial demands and offers presented, the verdict type, the jury vote, the jury composition, and the final outcome. It only takes a few minutes to sift through this data, which tells us that approximately 50% of the slip and fall cases in our sample resulted in mediated settlements.

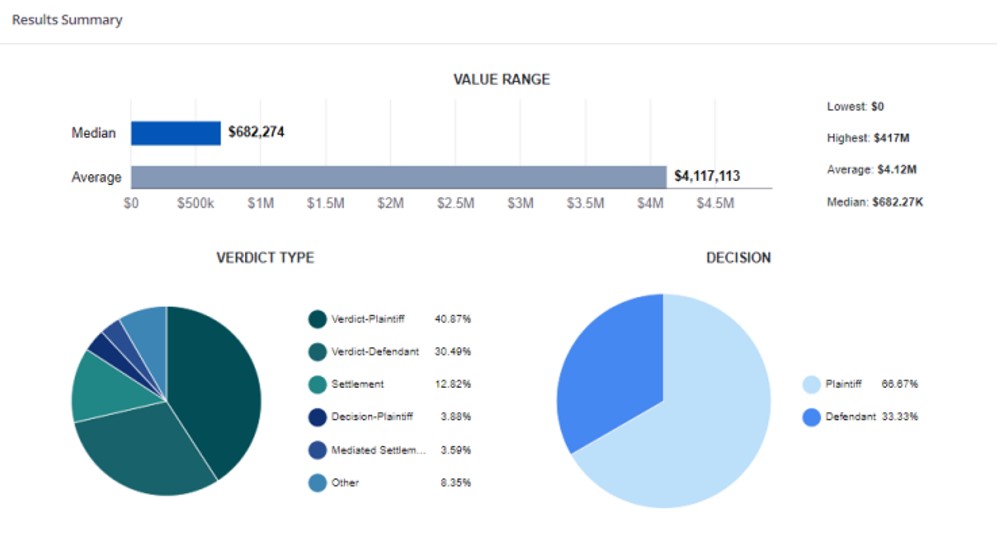

But what does this really tell us? What else can we learn by tracking case outcomes? According to Nick Reuhs, a partner at Ice Miller, “everyone’s going to use it differently, getting the different nooks and crannies of it.” As an insurance practitioner, Reuhs is frequently asked about limits. Clients want him to identify the outliers, the worst-case verdicts reached over the last three to five years.

“[But] if you get two or three hundred people to do something, you’ll wash out the outliers, and you can start to trust some of the statistics like the averages or median,” explains John Campbell, a former attorney at the Simon Law Firm in St. Louis.

With verdict analytics, attorneys are identifying the monetary amounts at stake in the settlement process, quickly getting a feel for the amounts different types of parties have been willing to accept in order to resolve different types of cases. Attorneys are then comparing these figures with the amounts awarded by juries, backing any possible counter offers with hard data about a case’s likely—rather than possible—value.

Behind the Runaway Jury

A hallmark of Anglo-American legal procedure, the jury remains a curious institution. It’s considered to be the backbone of our legal system, yet few appreciate just how rare jury trials have become. There has been a century-long decline in the portion of cases terminated by trial, with most disputes resolving through mediated settlements.

Legal analytics continues to bring new levels of transparency to these pretrial processes, the details of which are often hidden from the public record. The strength of this data lies not only in its transparency, but also its contextualization—its placement alongside hundreds of thousands of comparable data points. This is what the flashy headlines about nuclear verdicts and runaway juries miss. They miss the averages and the medians overshadowed by the infamous outliers.