This unsettled question has been in dispute since 2015 when two European dairy consortiums – one from Switzerland and one from France – filed an application with the United States Patent and Trademark Office seeking registration of GRUYERE as a “certification mark” for cheese.

This filing did not sit well with the International Dairy Foods Association (among others), so they opposed that application – and won on the basis that GRUYERE is understood by consumers to designate a category of cheese that can come from anywhere (in other words, GRUYERE is generic for cheese and thus unregistrable).

In response, the two European dairy consortiums filed suit in the Eastern District of Virginia to settle the issue of whether GRUYERE is a common name for cheese, or whether it indicates a cheese produced in the Gruyère region of Switzerland and France.

What Is a Certification Mark?

A certification mark is a category of trademark registration where an organization (who owns the certification mark registration) certifies that the entities using the certification mark follow clear standards or criteria for using the certification mark. For example, the Underwriters Laboratories certification mark “UL” indicates that a product has met certain safety standards established by Underwriters Laboratories.

So, What’s the Big Deal?

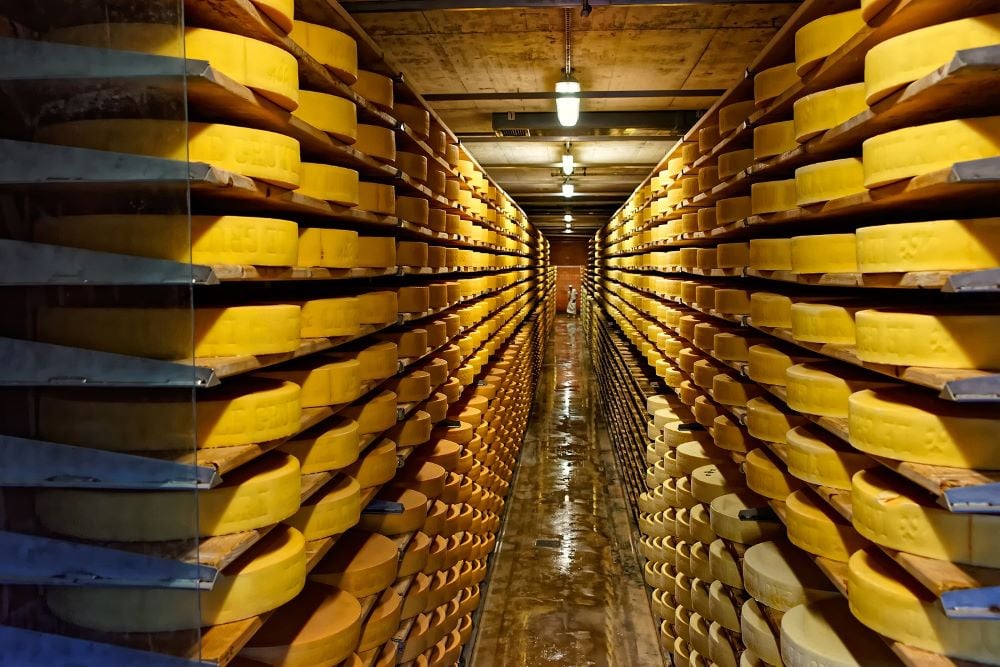

In this cheesy case, a U.S. certification mark registration would have established that cheese sold in the U.S. and labelled as GRUYERE cheese could only come from the Gruyère region of Switzerland and France. As such, United States producers could not label their cheese as GRUYERE cheese since it did not come from the Gruyère region.

This means the United States producers would have had to use another way to identify such cheese, such as calling it a “hard yellowish Gruyère-like cheese” which, admittedly, is quite a mouthful. The certification registration would not have stopped the making of such a cheese in the U.S., but it would have chilled production of this cheese since the U.S. consuming public would have to be reeducated about what to call such cheese (as a side note, the U.S. Department of Agriculture has certain standards which must be met for Gruyère cheese to be called “Gruyère”).

The Ruling

To complete the litigation saga of GRUYERE cheese, the two European dairy consortiums lost the district court case (on summary judgment) and then lost an appeal to the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled in 2023 that the term GRUYERE as applied to cheese is generic (a common name). Therefore, any United States producer or importer of such a cheese, provided it has met USDA standards, can call it “Gruyère cheese” regardless of where it is produced.

Geographical Indication in EU

However, these decisions are only effective in the U.S. In the European Union, protection called geographical indication (GI) prevents United States producers from exporting cheese called “Gruyère” to the EU. GI is a form of intellectual property recognized by the 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS), that protects terms that identify a region in which a product is produced.

The U.S., having signed on to the TRIPS agreement, is required to protect GIs. Examples of GI protection in the U.S. include “Idaho potato.” You say Idaho, we say potato. Other U.S. examples include “Washington apples” and “Florida citrus.” You cannot call an apple grown in Michigan a “Washington apple.”

A Cheese Dichotomy?

The term ROQUEFORT is protected by a U.S. certification mark registration (U.S. Reg. 571798) obtained March 10, 1953. So, how can the ROQUEFORT certification be reconciled with the decision that GRUYERE is generic? The ROQUEFORT certification mark registration was obtained before other producers started calling U.S. cheeses “Roquefort.” These two European dairy consortiums simply waited too long to file their claim to certification mark rights in the United States! They let the milk cows out of the barn and couldn’t get them back in.

Just one more reason to file as early as you can!