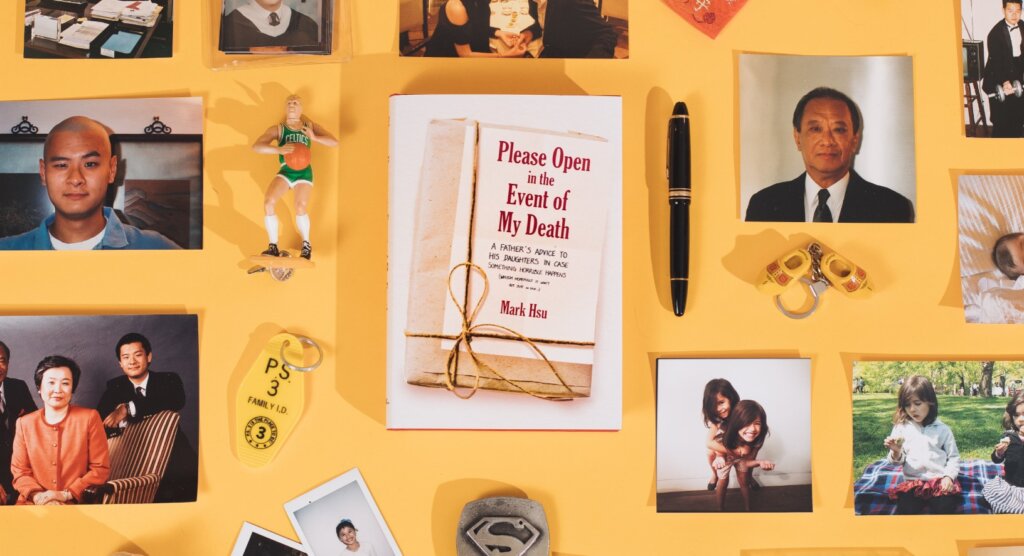

Litigation partner Mark Hsu was consumed with the thought that if his plane went down during one of his business trips, his daughters, 3 and 4 years old, would not remember a single thing about him.

Hsu proceeded to write Please Open in the Event of My Death, a compilation of advice addressed to his daughters but geared toward adults. He wants to tell his girls about the unwritten rules of the world and the hard-earned lessons one has accumulated by a certain age, touching upon everything from character to friends to fear to social facility to work success to marriage to kids – a Manual for Life.

Throughout, Hsu weaves in his personal experiences and memories, as well as a number of sports and pop culture references. He recalls his lonely, peripatetic youth in Japan, Italy, and all over the East Coast as the only child of a deep-cover CIA spy; he recounts all-too-familiar work experiences as a longtime New York City attorney; and like any person juggling work and home, he has some grossly incompetent parenting stories to tell.

Out of all of the personal attributes that can be used to define a person, Hsu chooses three he’d want his daughters to have in the following excerpt from the chapter “Describe Yourself in Three Words.”

Once you go on interviews for work, you may get a question like the above.

It will most probably be for an entry-level job, because this question is kind of lame. It’s well-nigh impossible to describe yourself in three words. And merely saying these words doesn’t make it so. The purpose of the question is not to necessarily find out about you, but rather what’s important to you, what you think of yourself, and what you want others to know about you. If other people are asked what three words would best describe you, I would want them to mention a variation of the following. These are the qualities that must reside deep within you and constitute your very essence.

Humble. Honorable. Kind.

I can already sense how underwhelmed you are.

Yes, these qualities must sound incredibly trite and sappy and easy to follow. The part about them being trite and sappy is true; the second part about them being easy to follow is absolutely false. It actually becomes more and more difficult the older you get. As a matter of fact, in trying to show you how difficult it is to be all of the above, I may end up convincing you that it’s easier and more profitable to be an arrogant bastard with a complete lack of morals. Let’s see how I do.

“HONORABLE”

You must lead a life of integrity. I demand it of you.

It certainly sounds great. “Alessandra and Sofia are such women of integrity.” Man alive, I’m swelling with pride just reading that sentence. I know “Alessandra and Sofia are so gorgeous” probably sounds cooler to you, but believe me, you want people to be saying the first sentence.

Honor or integrity is hard to define. It certainly starts with being honest. My parents drilled this into me: without truth, you cannot have trust. We have already had that first conversation with you after we’ve caught you in a lie (and remember that if you ever have that talk with your child, you CANNOT break and laugh out loud when she’s got pineapple candy wrappers strewn all over her bedroom while insisting that she didn’t have any). Honesty is the touchstone of an upstanding person, someone with morals. In law, if someone testifies under oath and is untruthful about a material detail, the jury is entitled to disregard the entire testimony, because that person is no longer reliable. Without honesty, everything you say or do becomes suspect or comes under a qualifier. It seals the authenticity of a promise and the security of a secret.

Parents telling their child to be honest is not unusual, except that my father—the grandfather you never met—was a spy.

He was a deep-cover intelligence officer for the Central Intelligence Agency for 20 years. Just being able to say that he used to work for the Agency was significant, because not many operatives get to have an overt retirement. He was finally able to tell anyone what he used to do, with much pride. (The flip side of this overt retirement was having to go on an apology tour afterward to all of our friends and family about deceiving them as to his profession and background.)

He was a NOC, “Non-Official Cover.” You know that scene in the first Mission: Impossible movie where Tom Cruise is dangling from those cables and trying to upload information onto a floppy disk without triggering sound, temperature, and touch meters? He was getting a list of NOCs around the world. In this preposterous scene in this completely absurd movie, YOUR GRANDFATHER WOULD HAVE BEEN ON THIS LIST.

There was no choice but to deceive when his job entailed getting information from allies and enemies alike; even to close acquaintances he was often untruthful about his motives, his profession, and even his name. Being a NOC meant that he was not affiliated with the U.S. Embassy, so if he happened to be detained by a foreign government, he was essentially on his own, with the U.S. government in all likelihood issuing some sort of a terse disavowal of any spying activity conducted by this person.

If my father told the truth or even engaged in candor at the wrong moment, everything in his life would have been compromised—his life, his freedom, his livelihood, his family. Precisely because he knew the cost of deception to a person’s reputation, he insisted that I be honest, to tell “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.” By and large, I’ve dutifully followed this directive, even though it’s probably hurt me professionally. People can tell when you don’t truly believe what you’re arguing or negotiating. But when you have a reputation for telling the truth, it allows you the benefit of consistency, which anyone, even an opposing attorney, can appreciate. There isn’t second-guessing of what you really mean. There shouldn’t be any further delving into your motives. Yes, I understand this is all incredibly hypocritical coming from a litigation attorney whose very existence depends on the parsing of words and who trades in half-truths and concealment of weaknesses (and those are the more scrupulous ones! The dirtbag attorneys just baldly lie and bank on the truth not coming to light).

This was also what my father drilled into me: the cover-up of a lie is usually worse than the lie itself. This was a lesson primarily learned during Watergate, but it resurfaces time and again. You’d be surprised at how insignificant the original sin was and how willing the public would have been to forgive it. But when you double down and insist that you were telling the truth or otherwise lie even more to cover, and then you’re found out…you’ve lost all credibility. Good luck getting that back. It is not possible to lose your reputation twice.

You can’t have integrity without truth, but its limits do not end there. You can be stridently honest but not necessarily have integrity. For example, if pressed by others, you may answer that yes, you believe that there is a certain social injustice occurring. That’s being honest. But to have integrity? You need to go beyond, to consistently stand up for the upstanding moral principle—no matter the ridicule, the sacrifice of money, even the tide of popular opinion. By the time Muhammad Ali died, it was easy for people to laud his courage in refusing to serve in the army and being a conscientious objector. Back then, though, would they have supported him?

One area where you can gauge a person’s integrity is responsibility/credit/blame. If you’re going to be working with others, there may come a time when you have to take responsibility for which you personally did not do anything wrong. Yes, we missed the deadline to appeal because the wrong date was calendared. Technically, this was the clock-watching, Facebook-checking, meaningless-tweeting, dumbass paralegal’s fault. But you, as the one supervising this person—who had ONE JOB THAT HAD TO BE DONE RIGHT, JUST ONE—this is where you will have to fall on your sword, take that bullet, and endure the beating. Apologize unreservedly and with sincerity, without resorting to bullshit weaselly language. Oh, it’s massively unfair how painful it will be. You will suffer (it need not be done silently, as you can continually remind the dumbass paralegal what you did to protect him). But in the opinions of those who matter, you will emerge a better person and one with more respect.

When you two girls become older, you will get a sense of how competitive this world is, where people will put their self-interest above a code of conduct, and where people will point to others’ failure to adhere to the code as an excuse. I realize that insisting that you be women of integrity puts you in a position to be mocked long and loudly, probably more by your younger contemporaries. “You’re a sucker” is a retort that quickly comes to mind. Contrary to nearly every TV show and movie out there, most of the unscrupulous do not get their comeuppance in the end. The older you get, you see more examples of completely amoral behavior, and you may start to correlate the lack of integrity with the ability to ascend to certain work positions. Maybe by then, it really may not mean as much to be a person of integrity, as anachronistic as five-cent Cokes.

I don’t care. This has to be a fundamental part of your personality. You are not sheep. Look beyond the short term, and to your life, and be guided by a set of principles based in morality. Not all of these rewards will be readily apparent. But they will reap benefits for you. Because when you pass from this world to the next, people will not be focusing on your net worth, or how beautiful you were, or even what you accomplished. They will be primarily talking about the content of your character. Your sense of honor and how it manifested itself in the way that you treated your family, your friends, and those whom you barely remembered. Your name.